Random Quote Board

How to Measure Sinusoids and Noise Spectrally using Gnu Radio (Corrected)

UPDATE: 10 January 2026: The whole point of this post and the previous one was to deal with noise and power spectral measurements. Should have just looked online first. Neil Robertson has several posts over at DSP Related.com, including a general method for calculating spectral power, using the "pwelch" function to calculate power spectral density (PSD) (as well as another, more general method), calculating the power of a sinusoid in a spectrum, and his latest (done less than a week ago!) covering spectrum averaging. Having read through his posts, I've realized that you can accurately measure both coherent and noncoherent at the same time. It's based on how you measure the power levels (single point at the center vs the whole curve). I've reworked this post to better explain that.

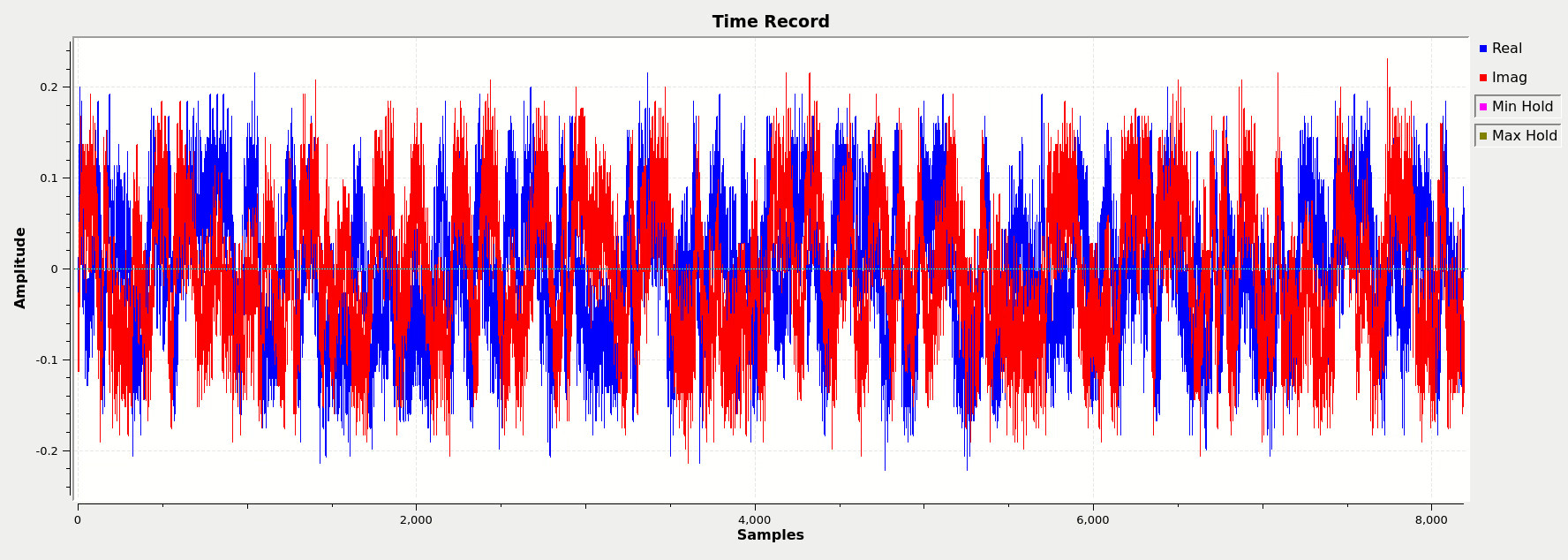

Happy New Year to you all! I'm going to finish up a few loose ends with respect to my last post discussing issues measuring SNR using a spectral display. For this post, I'm going to explain some of the complexity of measuring sinusoids and noise using the Gnu Radio QT GUI Frequency Sink.

In my original post, I looked at measuring signals based on whether they were coherent (a sinusoid or similar) vs noncoherent (aka noise). Now I'm just going to look at how you measure the signal whether it is as a single point (the peak measurement) or all of the points that make up that signal (band measure).

I'm going to boil down the problem of measuring power spectrally. It's spectral leakage. The typical "solution" for spectral leakage is windowing. To quote fred harris' paper[1]:

Windows are weighting functions applied to data to reduce the spectral leakage associated with finite observation intervals.

Spectral leakage and windowing create two problems with accurate spectral measurements. These are:

- Scalloping loss: This occurs due to the aforementioned spectral leakage, a problem that only occurs in DFT / FFT displays. You won't find this in analog spectrum analyzers.

- Window processing gain: Windows might alleviate some (or almost all) scalloping loss, but they also reduce the signal energy at the same time.

Windows have a slew of different parameters, which harris also covered in his 1978 paper. But two of the most important for measuring power spectrally are the incoherent power gain and the coherent power gain. The values can be calculated as follows:

Incoherent power gain = sum(w2)/N

Coherent power gain = (sum(w)/N)2

Think of these two values as "correction factors" that can be applied to the measured spectral power levels. But they're different values. So which one do you apply? You apply the one that you need depending on how you're going to measure the signal levels.

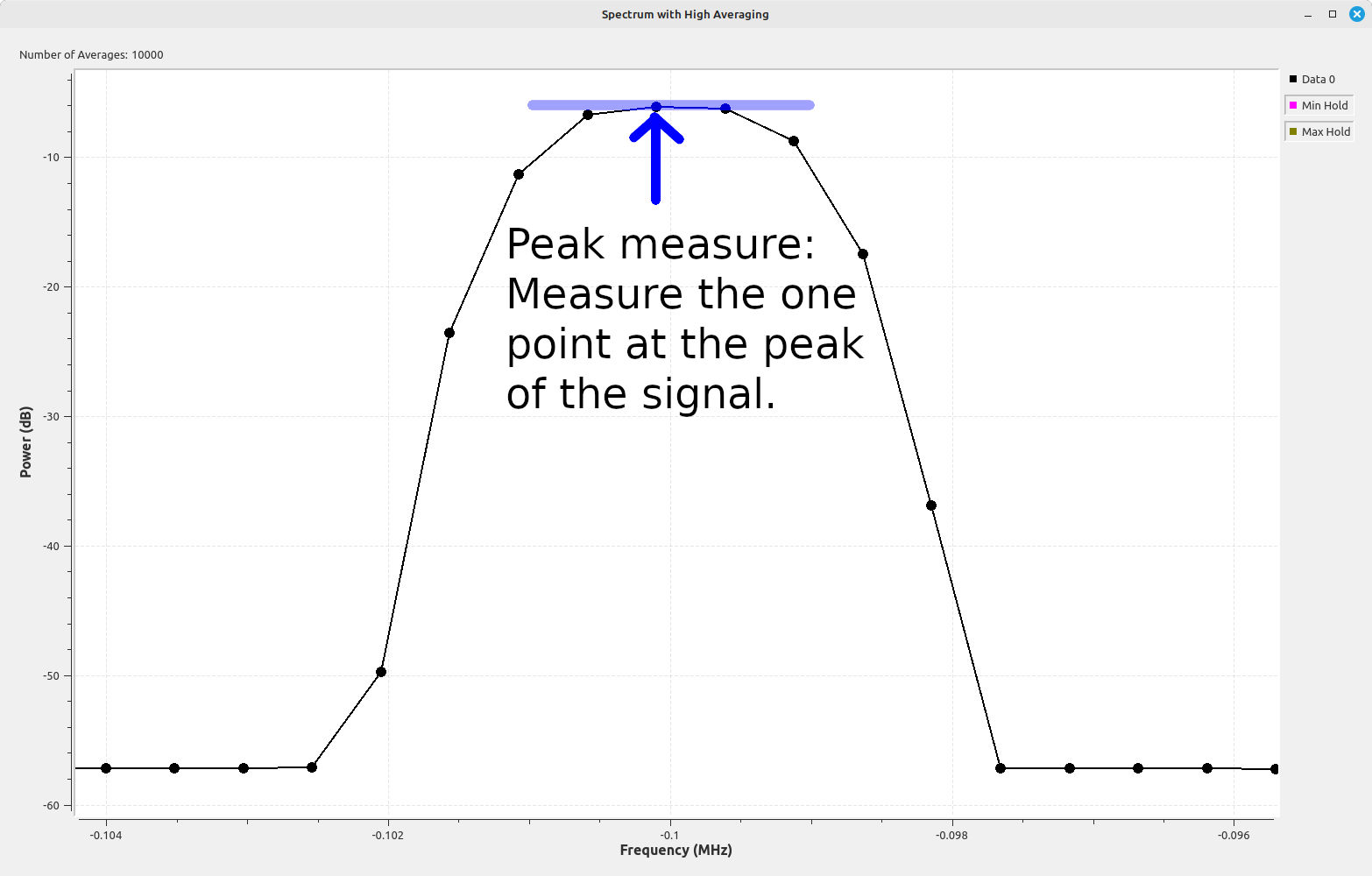

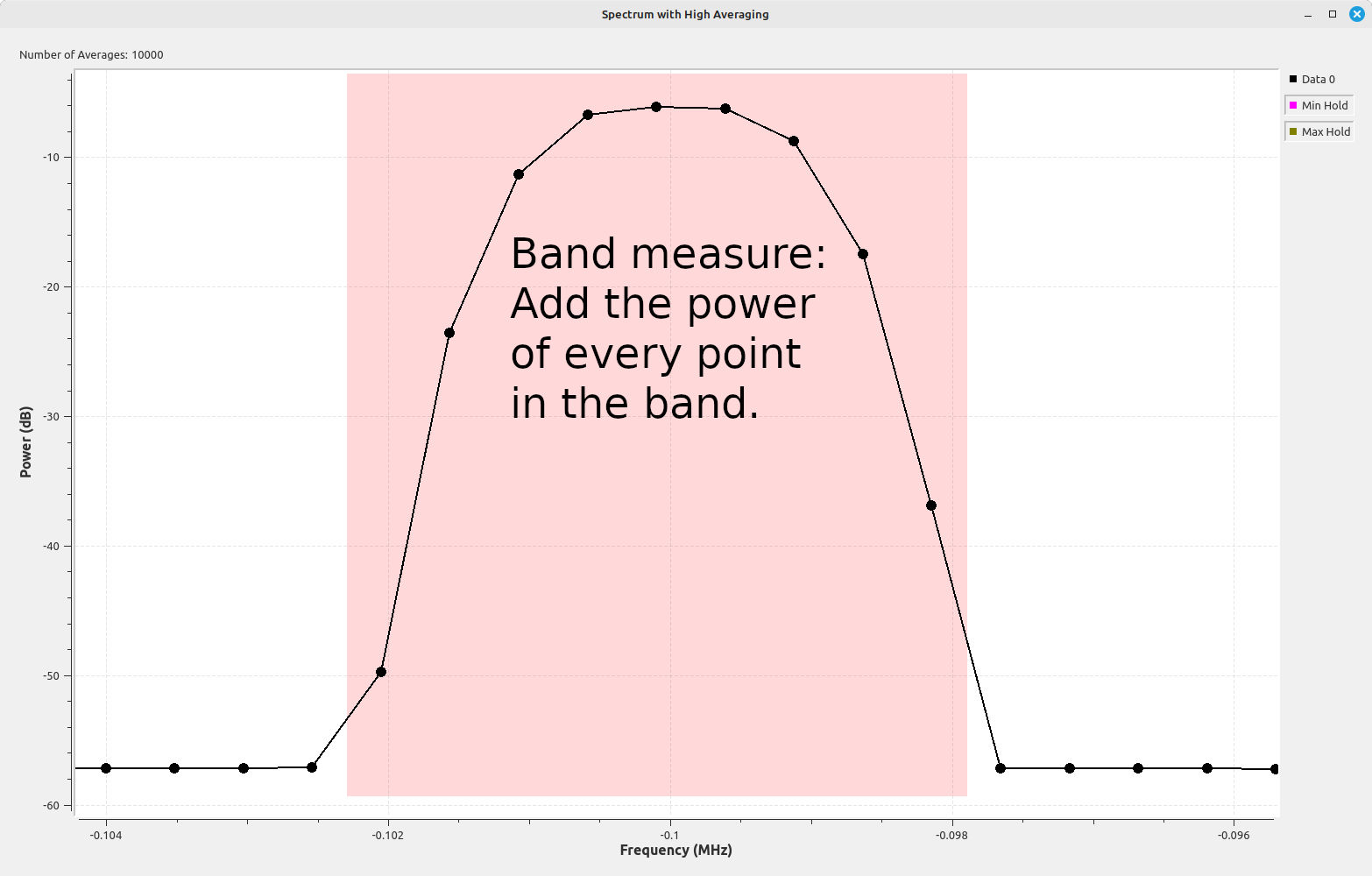

If you're going to measure the peak of the signal (say using a single marker that the spectral display may provide), then you'll want to use the coherent power gain. If you're going to measure the band power of the signal, meaning all of the points in the spectrum that make up that signal, then you'll want to use the incoherent power gain.

There's another value that's important with respect to these measurements. This is the normalized equivalent noise bandwidth or NENBW. This is the "window factor" that is used to calculate the resolution bandwidth (RBW) of the spectral display when using a specific window. The NENBW is typically expressed as a linear value, and is equal to the incoherent power gain divided by the coherent power gain. For example, the Blackman-harris window used in the QT GUI Frequency Sink has an incoherent power gain of -5.884 dB, and a coherent power gain of -8.91 dB. Since they are in decibels, we can "divide" by subtracting these two values, which gives us -5.884 - (-8.91) = 3.026 dB. In linear, this is 10(3.026/10) = 2.007, which is pretty close to the more-precise value of 2.0044 (given the issues of rounding dB values).

What we'll discover as we go along is that we can convert from one measurement to another using these different "correction" factors.

The incoherent power gain, the coherent power gain, the scalloping loss, and the NENBW of a window can be calculated. The values for most of the windows used in Gnu Radio are tabulated below.

| Window | Incoherent Power Gain (dB) | Coherent Power Gain (dB) | Scalloping Loss (dB) | NENBW (bins) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform (aka Rectangular) | 0 | 0 | 3.92 | 1.0000 |

| Hanning | -4.260 | -6.02 | 1.42 | 1.5000 |

| Hamming | -4.008 | -5.35 | 1.75 | 1.3628 |

| Blackman (approx) | -5.1627 | -7.54 | 1.10 | 1.7268 |

| 4-Term Minimum Blackman-harris | -5.884 | -8.91 | 0.83 | 2.0044 |

| Nuttall4b | -5.9205 | -8.98 | 0.81 | 2.01212 |

| Stanford Research Flattop ("Flat-top" in Gnu Radio) | -7.5593 | -13.32 | 0.0156 | 3.7702 |

Measuring Peak Power

Historically, systems were geared towards using peak measurements. For example, this FCC test report on a Kyocera cellphone from the early 2000s measured its output power using an analog-based spectrum analyzer. The analyzer's RBW has been set to be equal to the bandwidth of the cellphone's transmission (the curved line at the top of the display). This ensures it captures all of the energy of the signal. The user set the reference level (top line of the display) at the peak to measure its total power. Hence, this is a peak measurement.

Digital systems are different. Since each point on a digital spectral display is just a number, its possible to display the data however you want, then say, "How much power is in these points combined?" This is a "band measure", not "peak measure". For a computer, this is the proverbial "childs play". The problem is that, if you're not careful, measuring band power on a display that is corrected for peak power will give you incorrect readings.

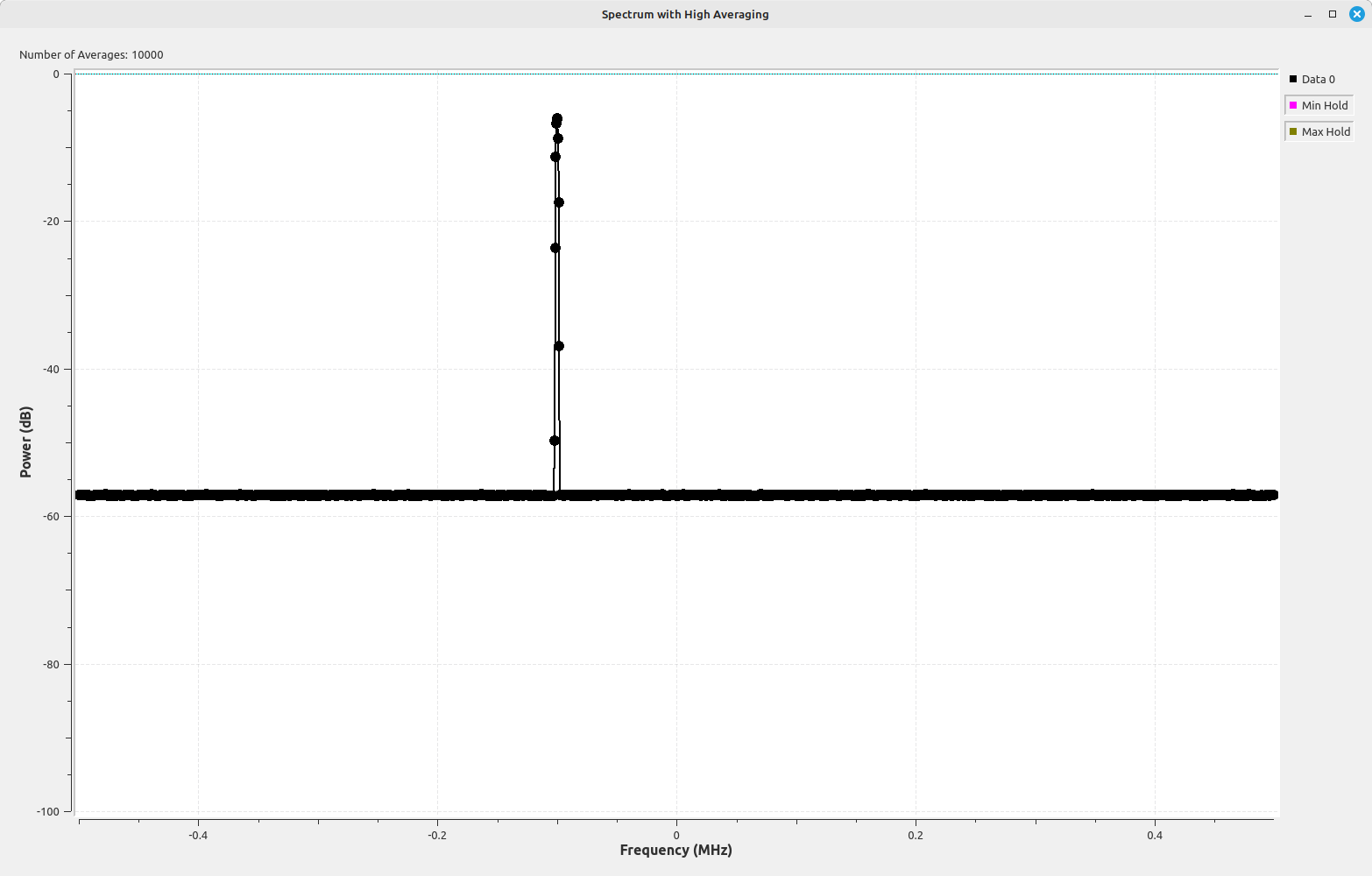

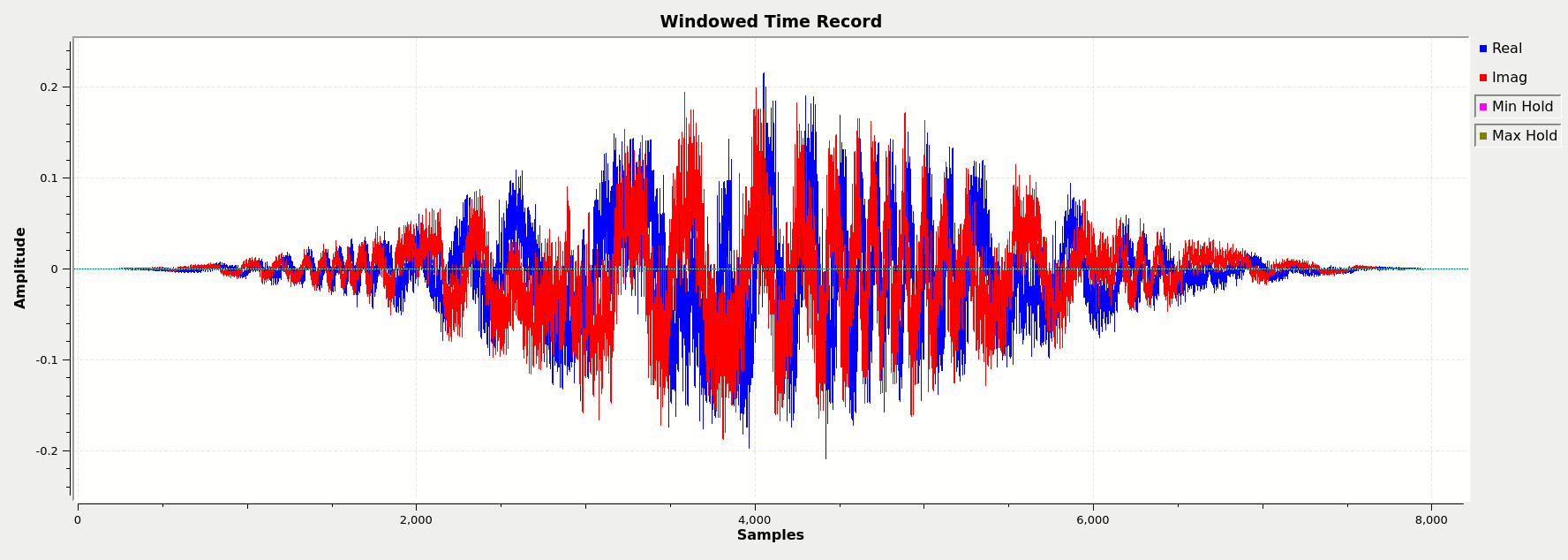

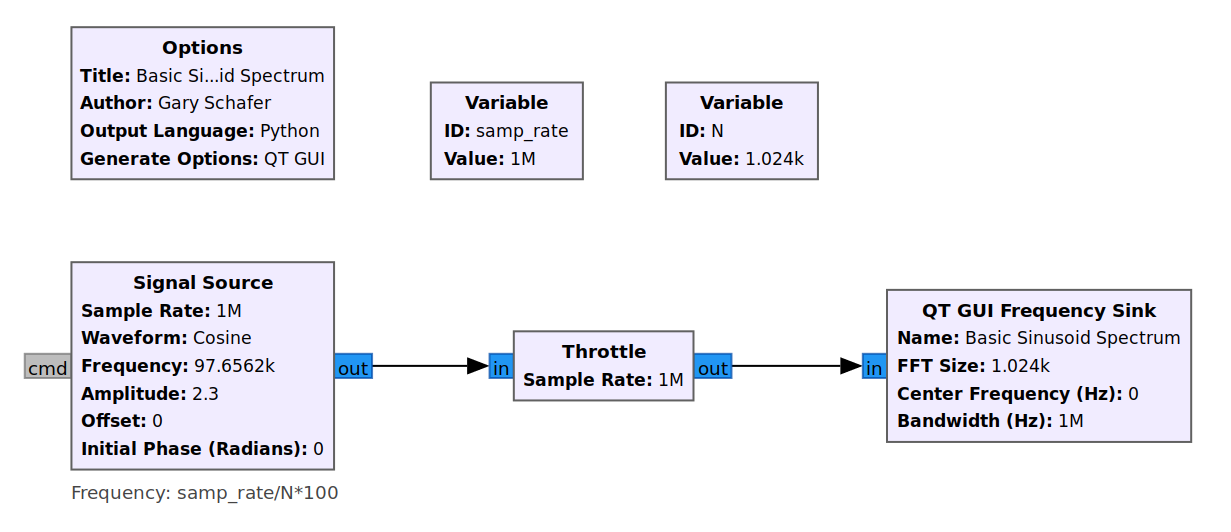

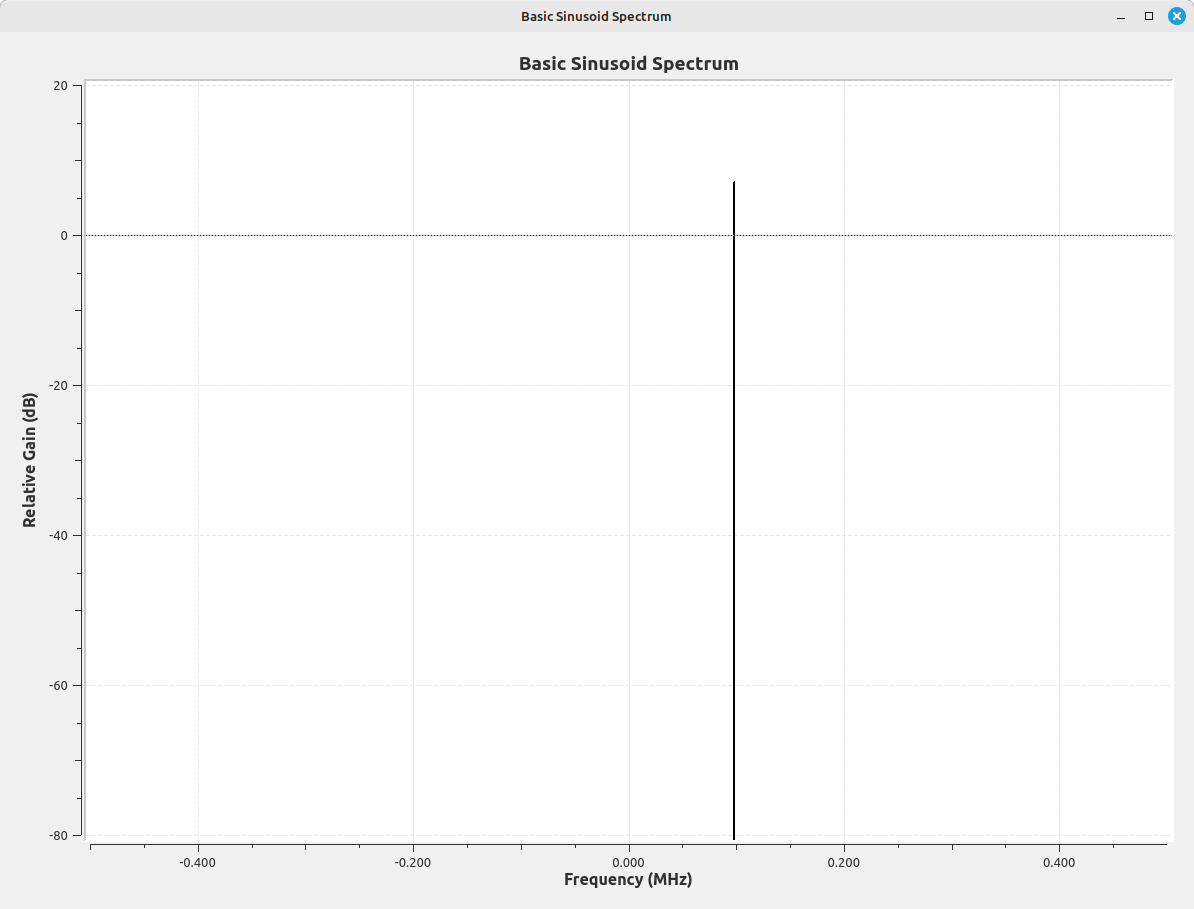

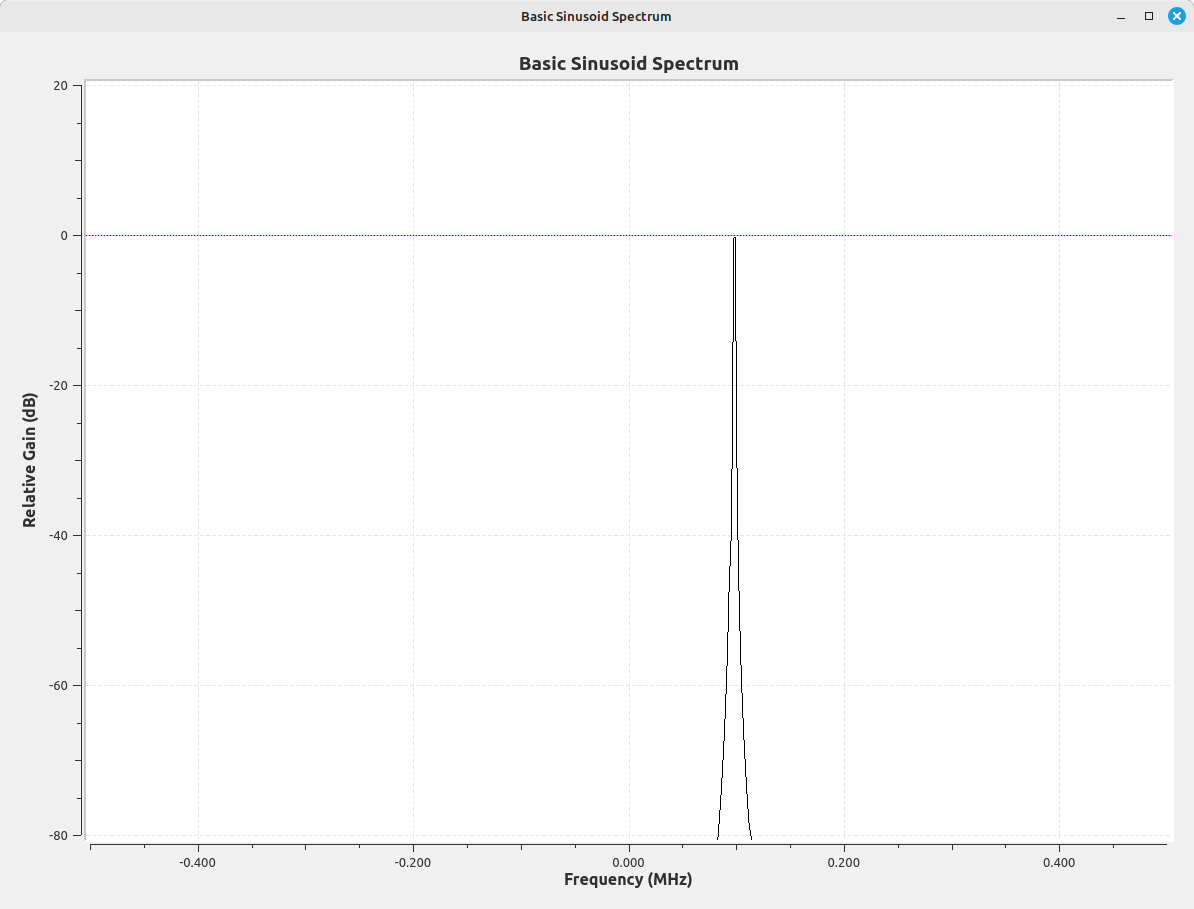

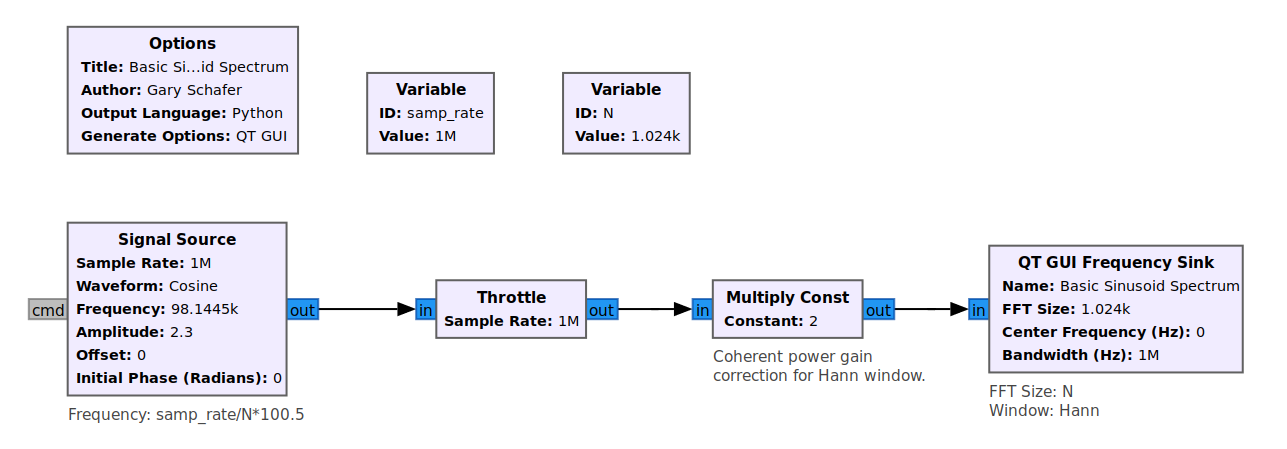

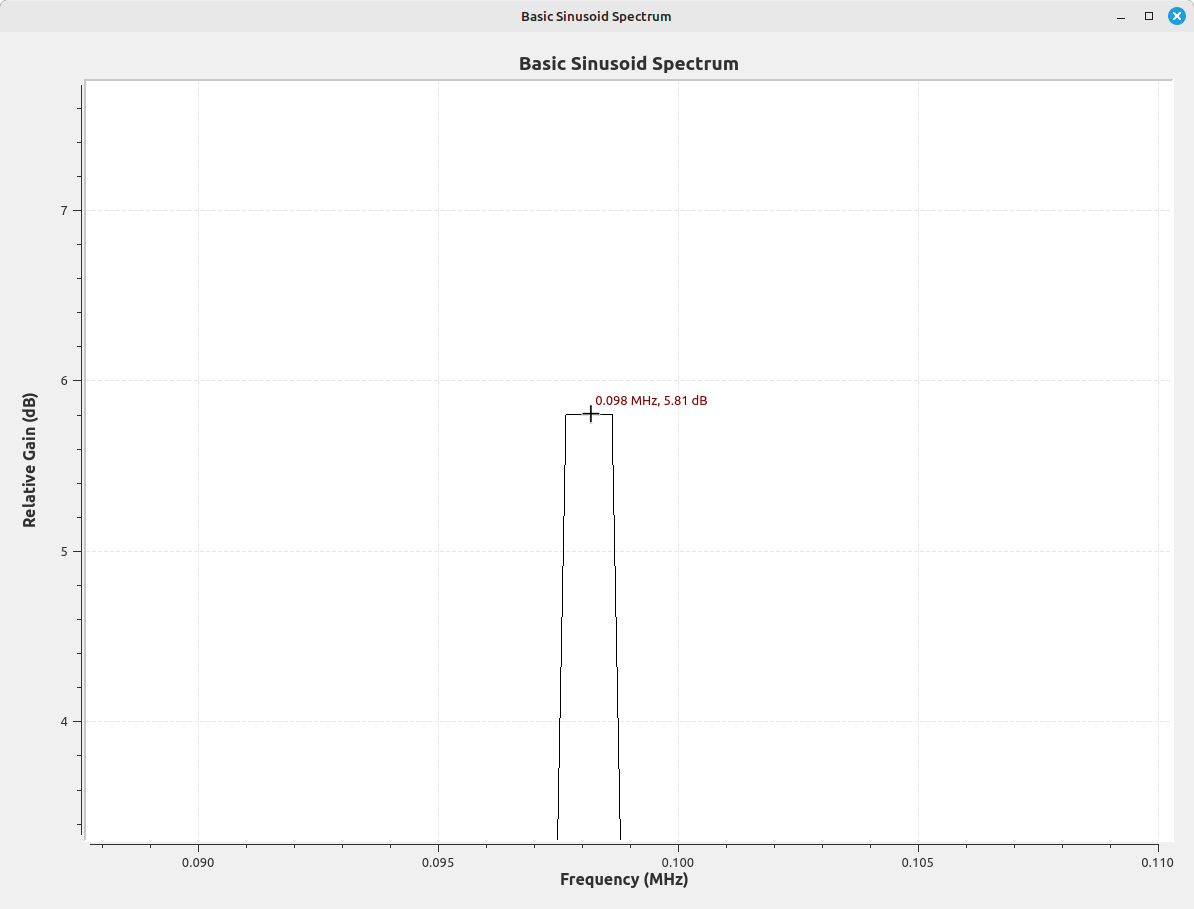

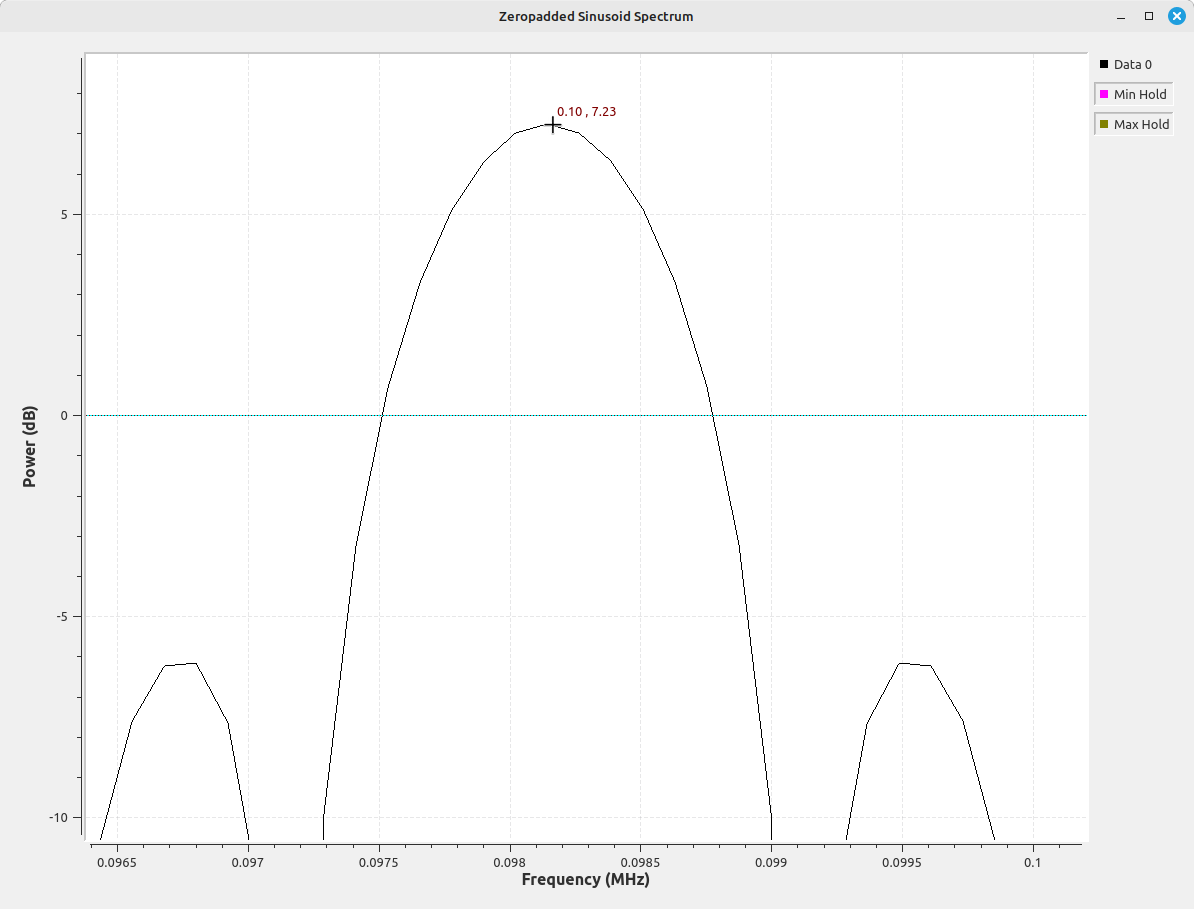

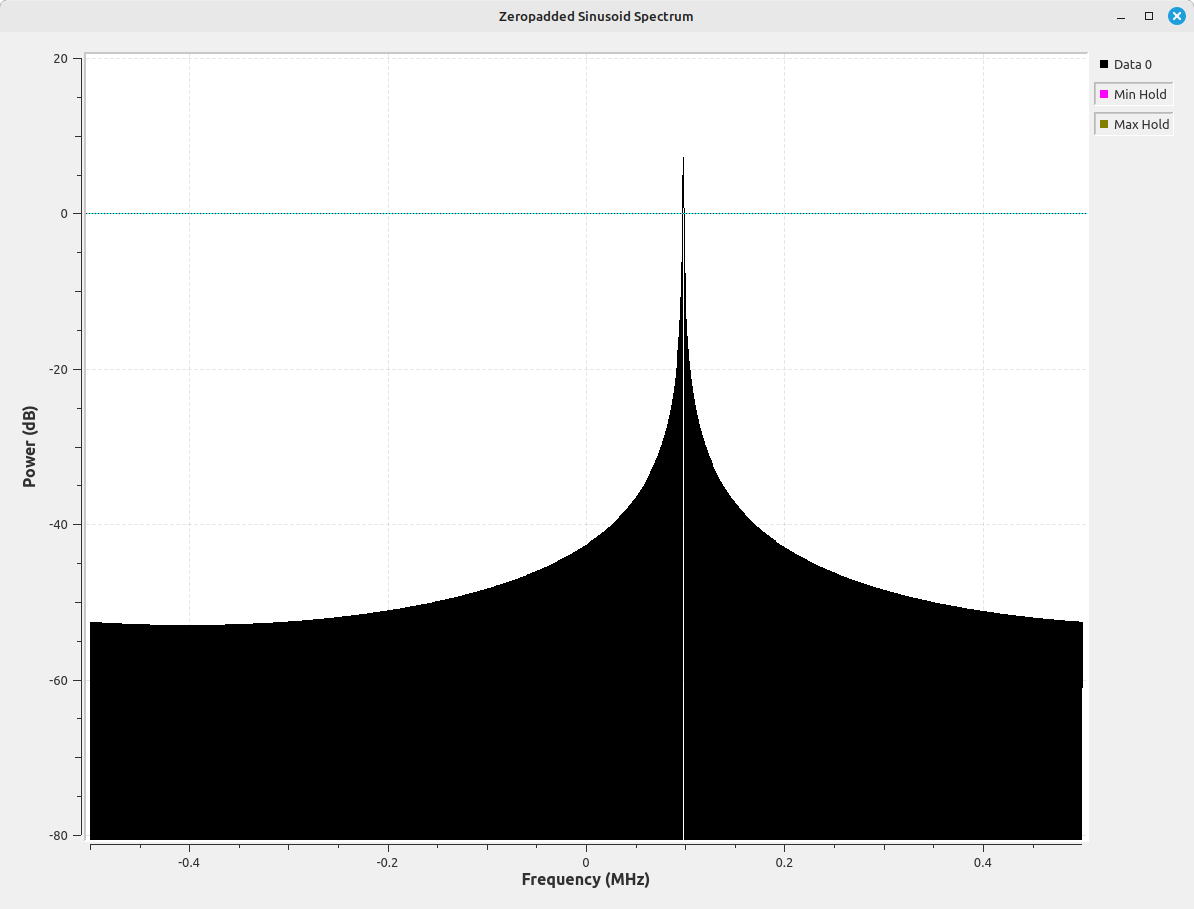

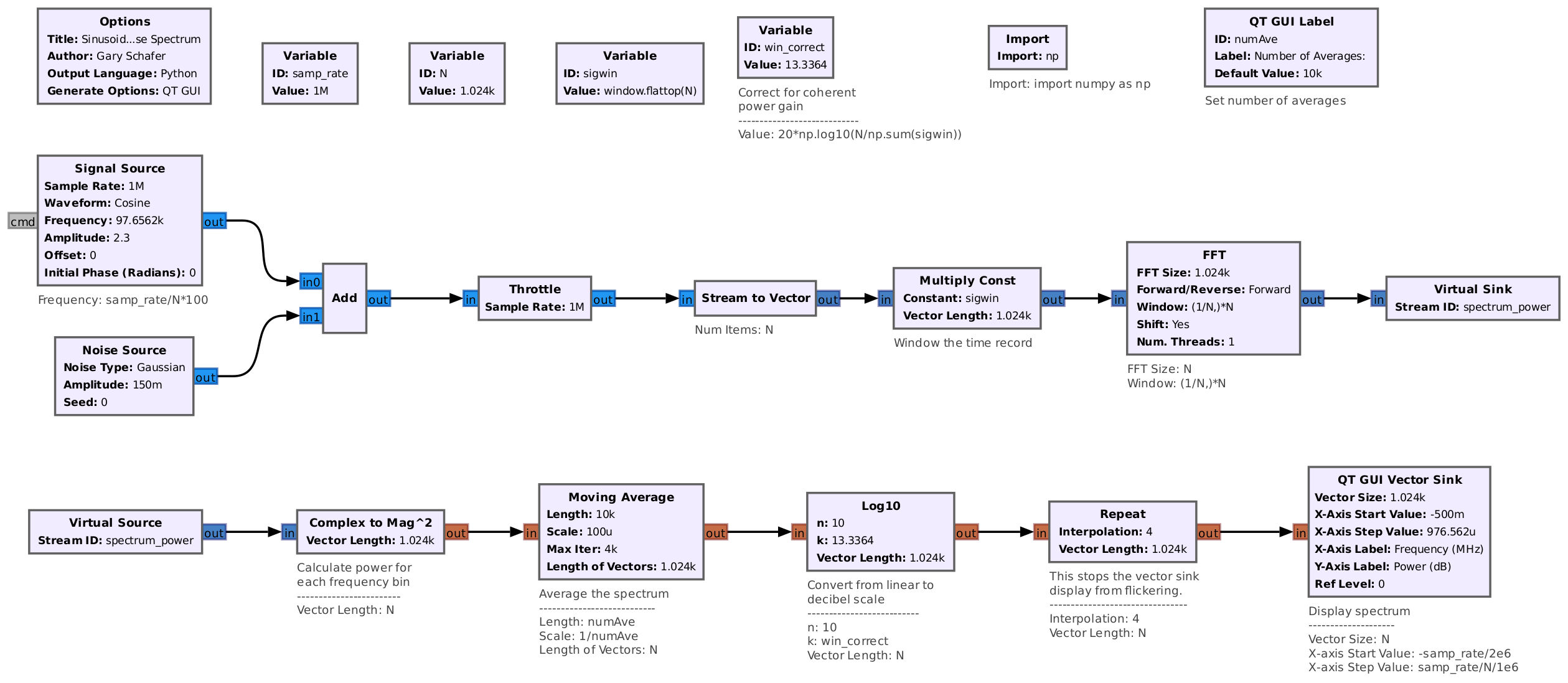

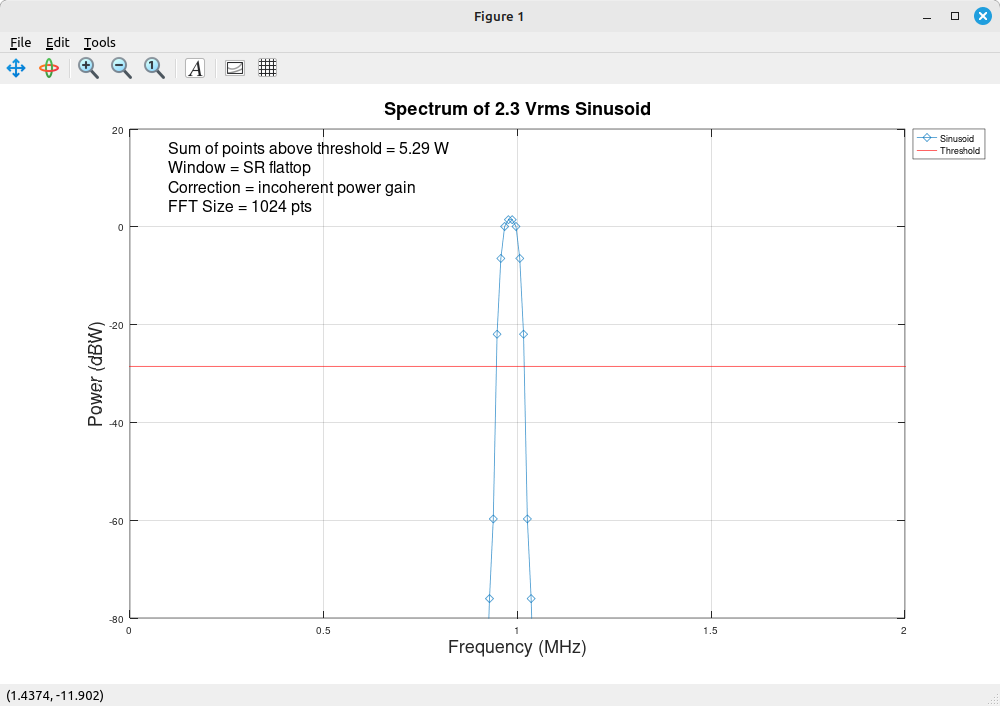

Let's start by measuring the power of a sinusoid. For this, I'll create a very basic flowgraph in Gnu Radio Companion (GRC). Below is the flowgraph and the initial display.

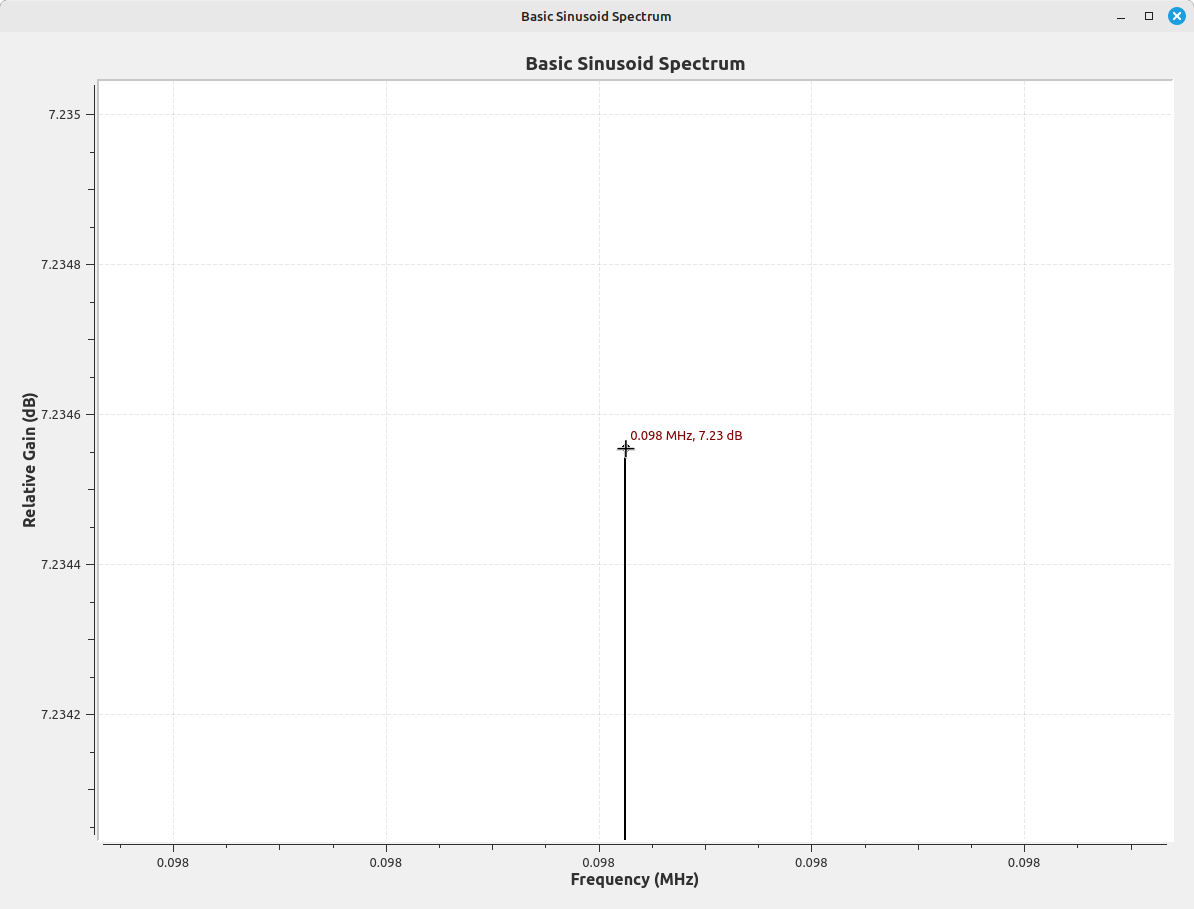

Again, the frequency display is set to be "unwindowed" (uses a "rectangular" window). If we zoom in on the peak of the displayed signal, it measures at 7.23 dB. This corresponds to the power of the sinusoid, which is set to a magnitude of 2.3. The linear power of the signal (assuming its going into a unity or 1 Ω load) is 2.32 = 5.29. Converting this to dB, we get 10*log10(5.29) = 7.23.

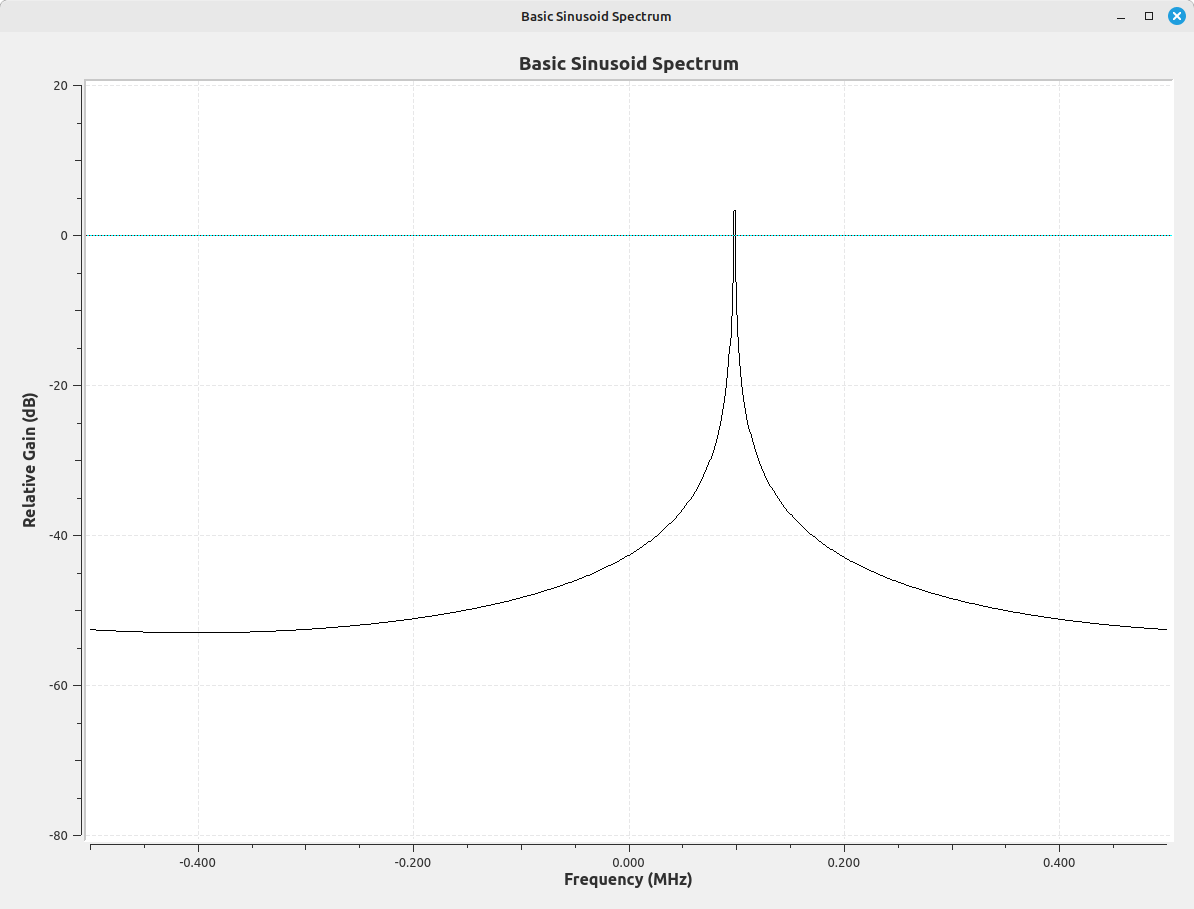

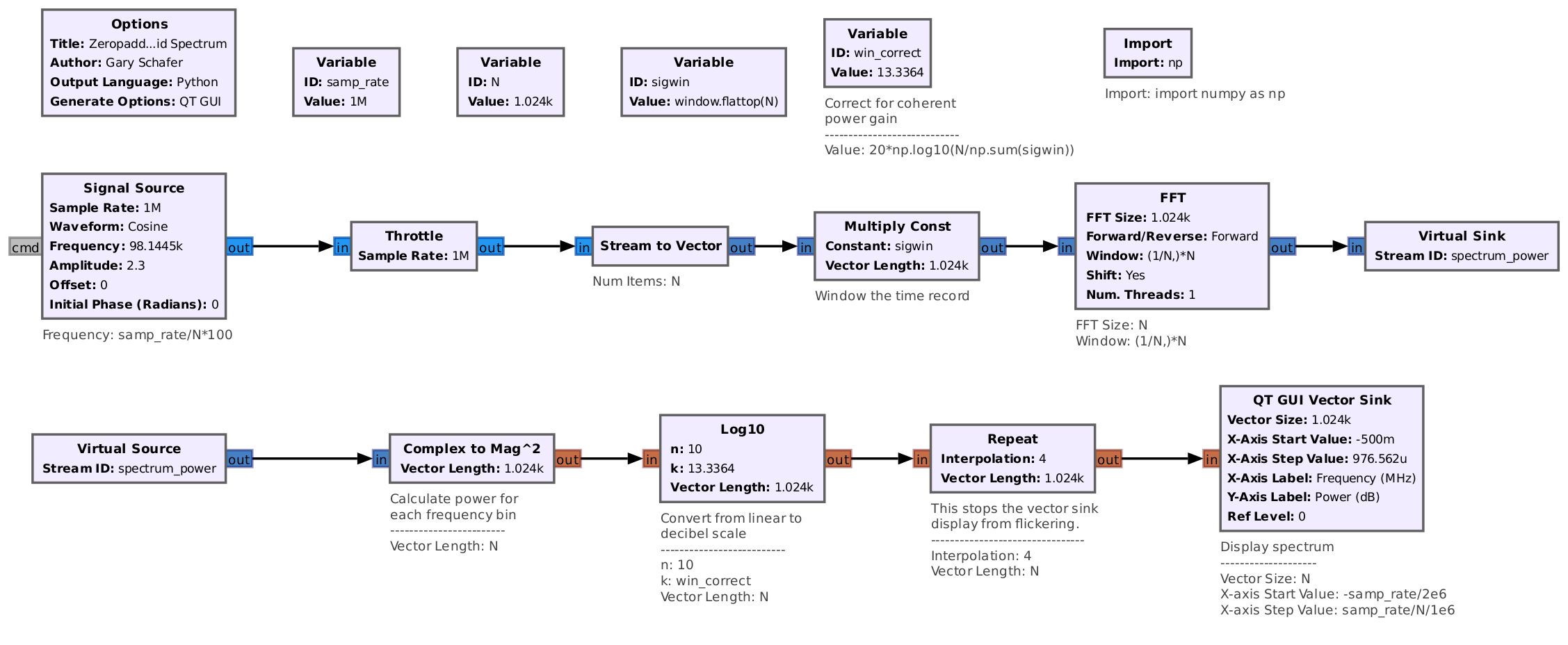

Now, what happens if we adjust the sinusoid frequency such that it is as the edge of a frequency bin instead of at the center? We get a mess is what we get.

With unwindowed signals, we wind up with a lot of scalloping loss (energy spread over the spectrum due to signals not being centered in frequency bins). Scalloping loss is uncorrectable. Hence, the introduction of windowing, the application of a weighted time series to reduce scalloping loss and spectral leakage.

Let's start with a basic Hann window. (NOTE: It's actually not a very good window, but it's easy to create and will demonstrate the important points.) We can create this window with the following equation:

w = 0.5 - 0.5*cos(2*π*n/N)

where:

- w = window values

- n = 0,1,2...N-1

- N = number of points in the time record

From these windows values, we can calculate the following parameters:

- Coherent power gain: This corresponds to the drop of the peak power of the signal. It can be calculated as (sum(w(n)/N)2. For a Hann window, this is 0.25 = -6.02 dB.

- Incoherent power gain: This corresponds to the drop of every frequency point of the signal. It can be calculated as sum(w2(n))/N. For a Hann window, this is 0.375 = -4.26 dB.

- Normalized Equivalent Noise Bandwidth (NENBW): This is the incoherent power gain divided by the coherent power gain. For the Hann window, this is 0.375 / 0.25 = 1.5 bins.

- Processing gain: This is sum(w)/N. This is 0.5 = -3.01 dB for the Hann window. This is the square root of the coherent power gain.

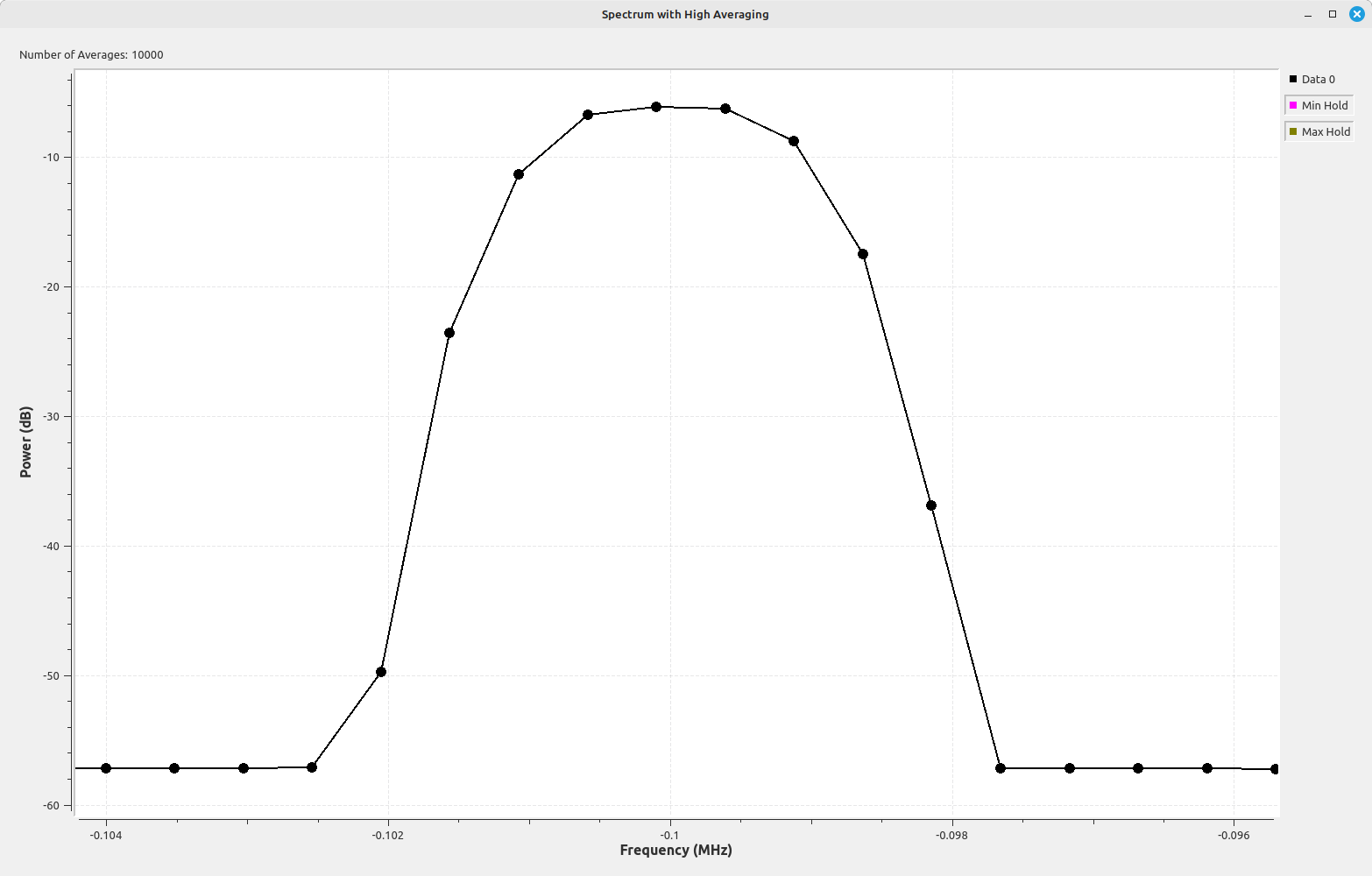

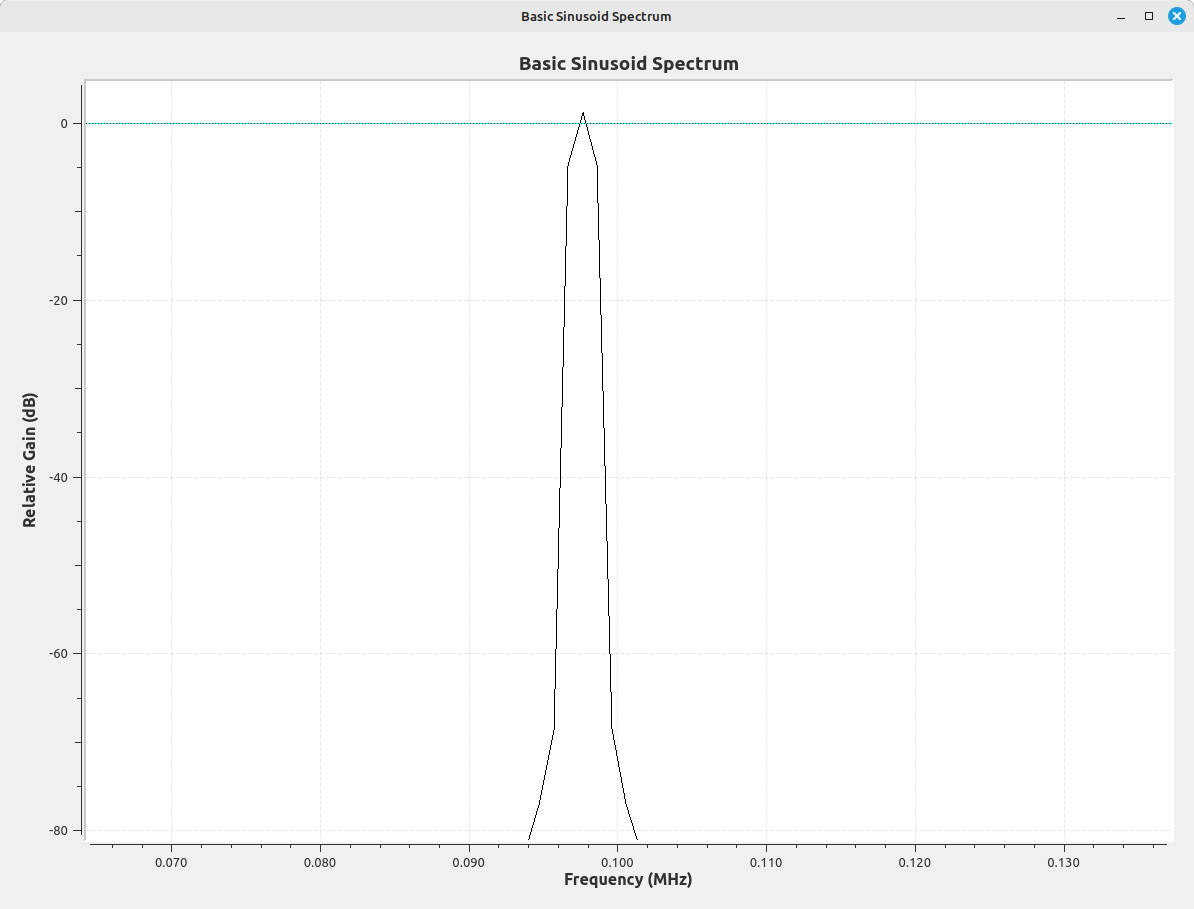

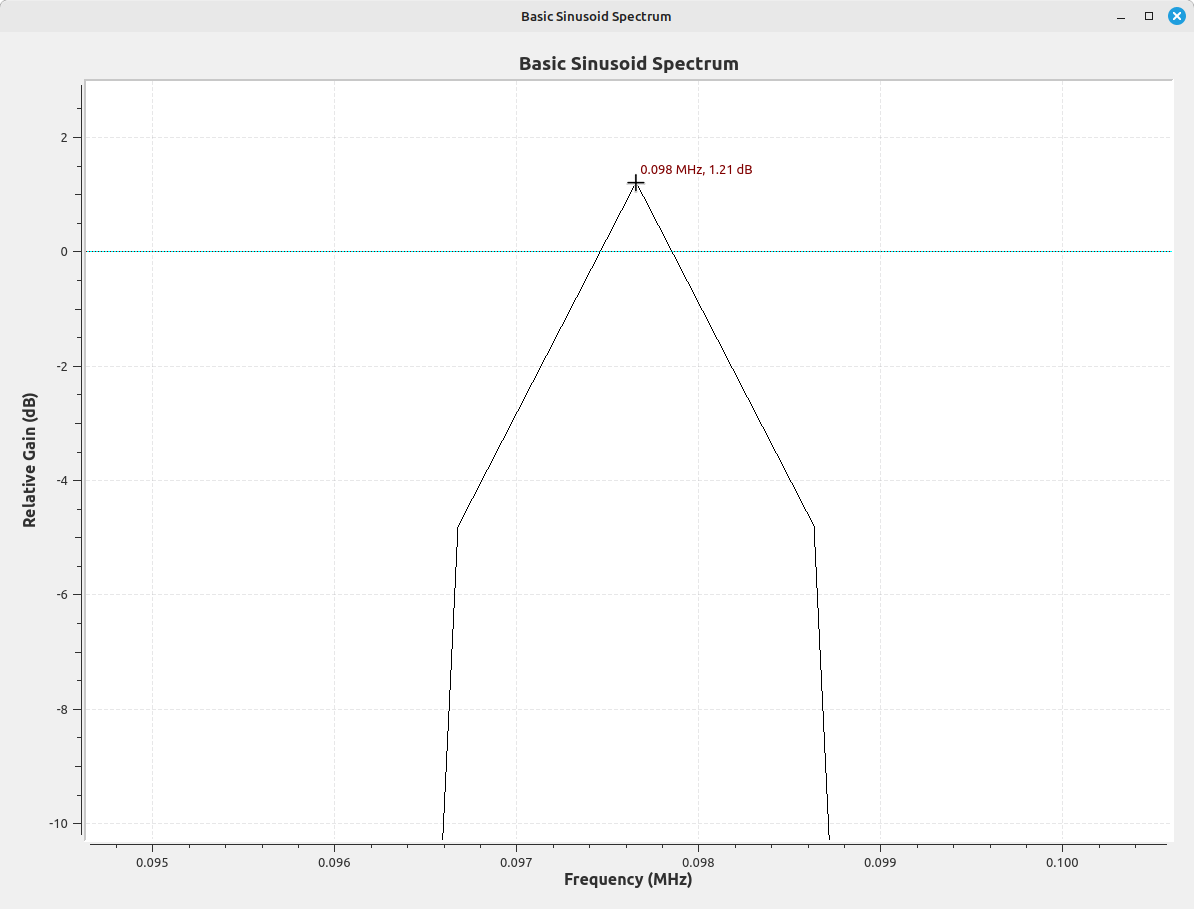

If we use a Hann window on our sinusoid, we get the following graph.

If we also use it on the non-centered sinusoid, we get the following:

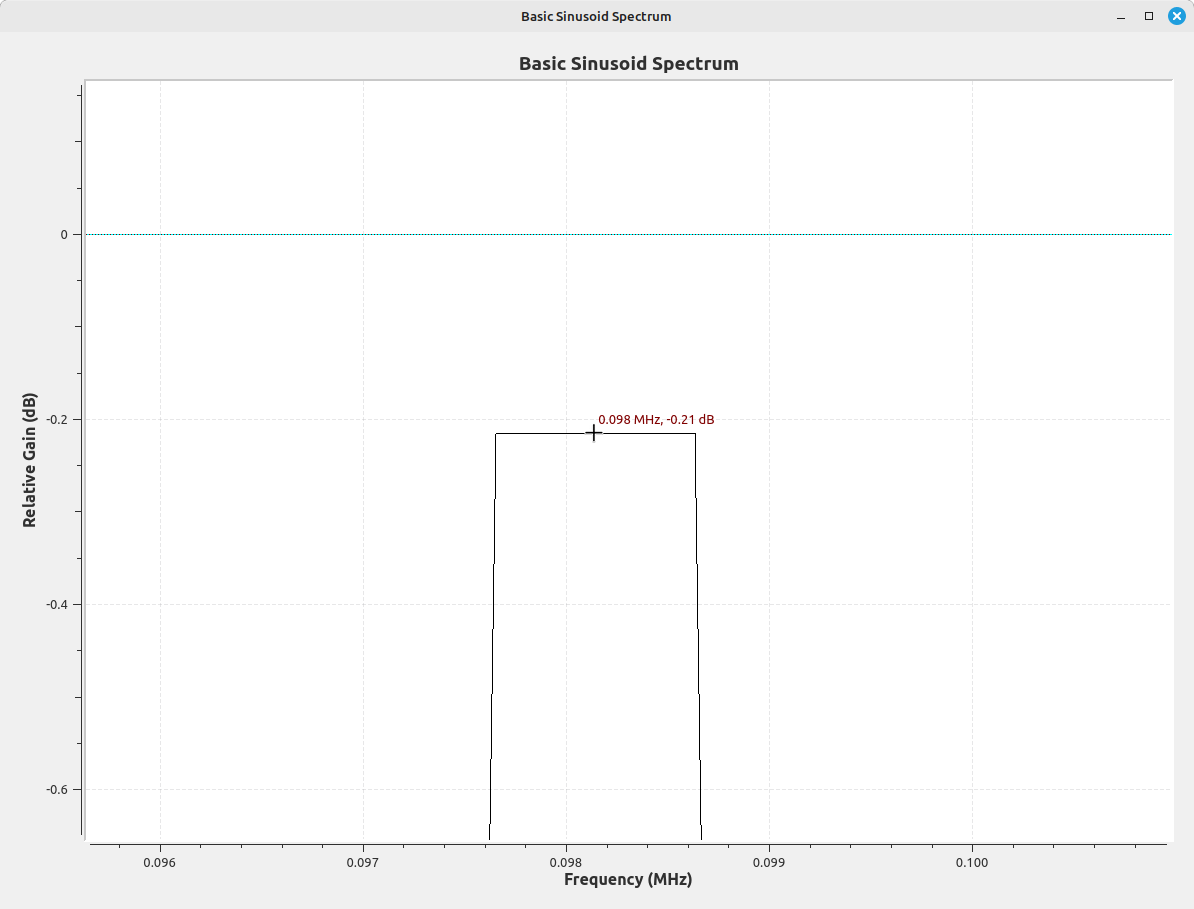

If we correct for the peak power, we can increase the amplitude of each point by 6.02 dB (multiply time domain samples by 2 to increase power by 4). This gives us the corrected spectrum, but there's still scalloping loss.

Correcting for Scalloping Loss

Even with the coherent power gain correction, the actual amplitude of an unwindowed, unmodulated tone can still be off by just less than 4 dB. Again, this offset is due to scalloping loss. There are a few, different ways to deal with scalloping loss. I'll look at two methods.

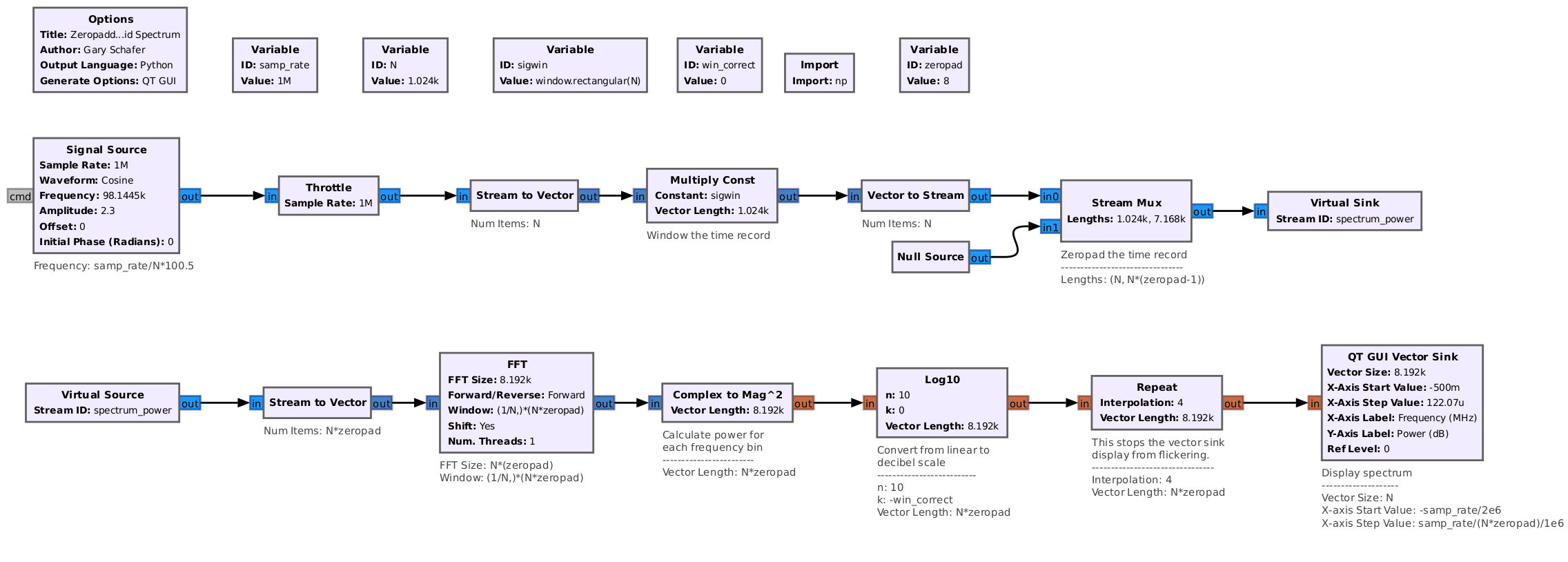

Zeropadding

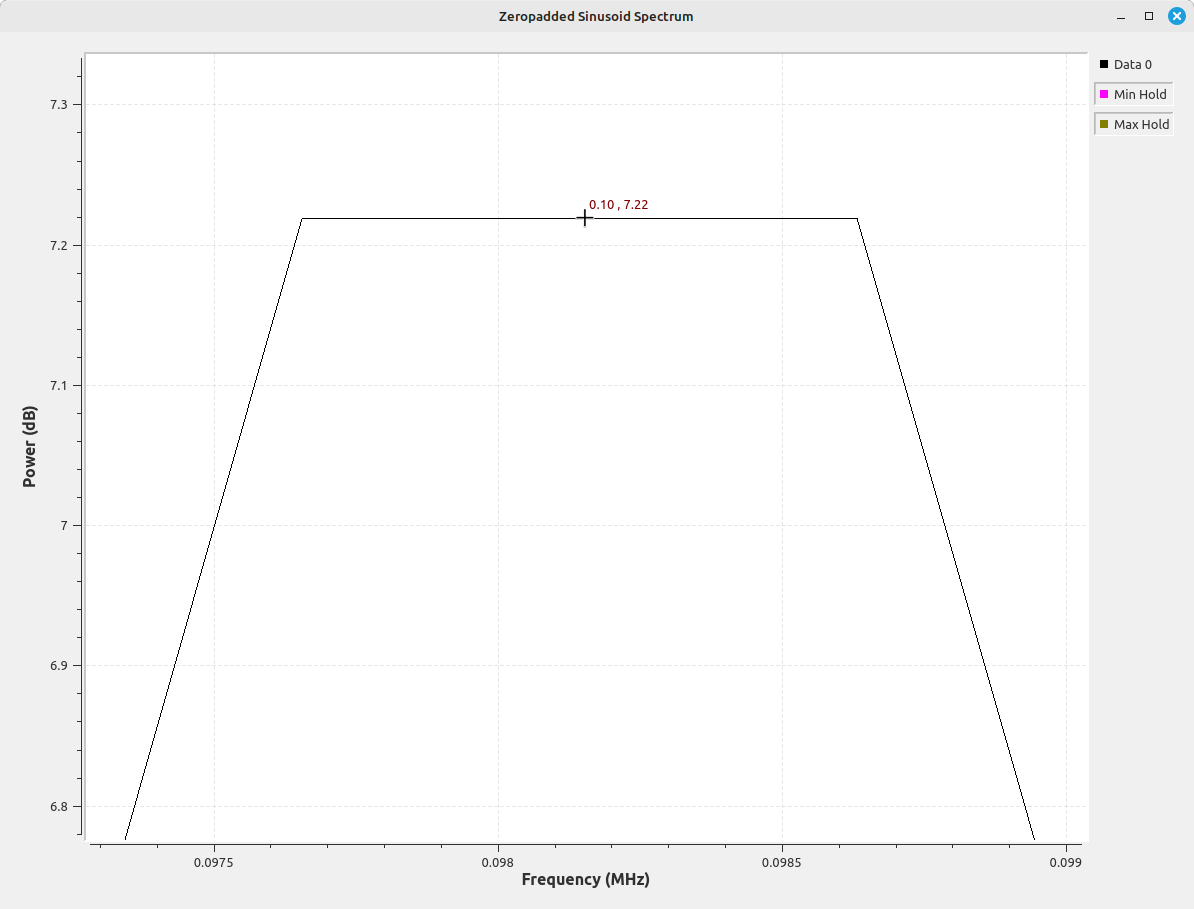

The first method involves zeropadding the time domain signal. The original signal is collected into a time record, windowed, then zeros are added to the end of the time record before it is fed into the FFT routine. This has the affect of interpolating in the frequency domain. To demonstrate this in Gnu Radio, I can't use the "QT GUI Frequency Sink" as it provides no method to zeropad the time record. I've created a new flowgraph that implements a frequency display, but with the ability to zeropad the time record.

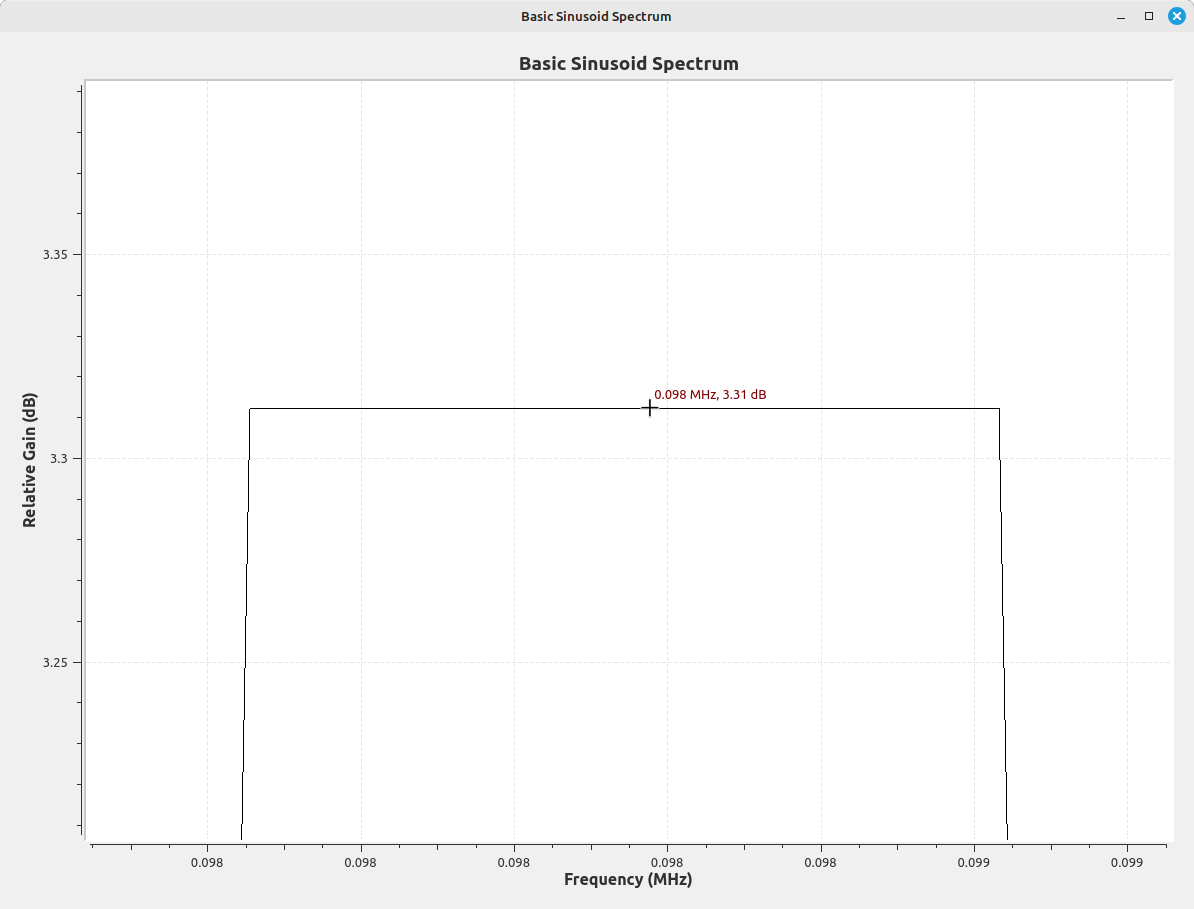

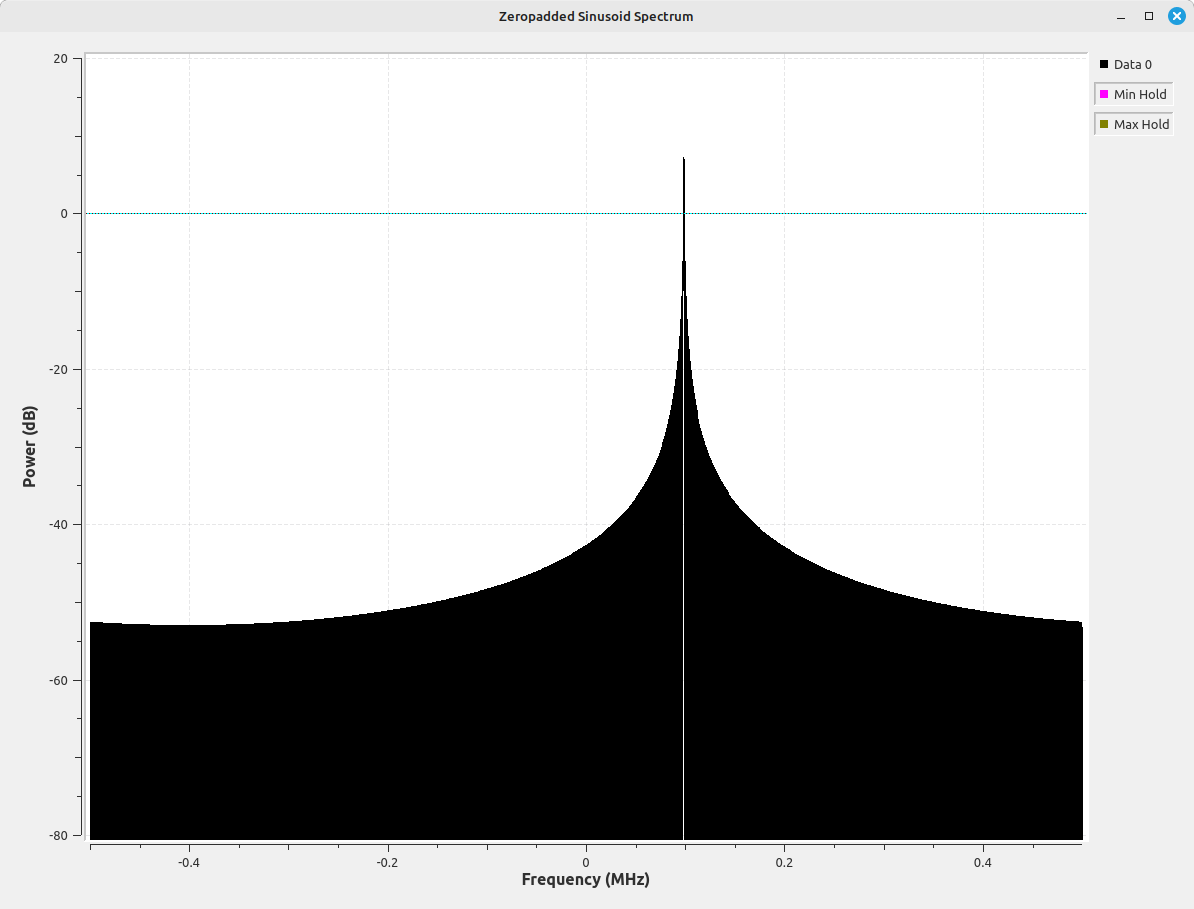

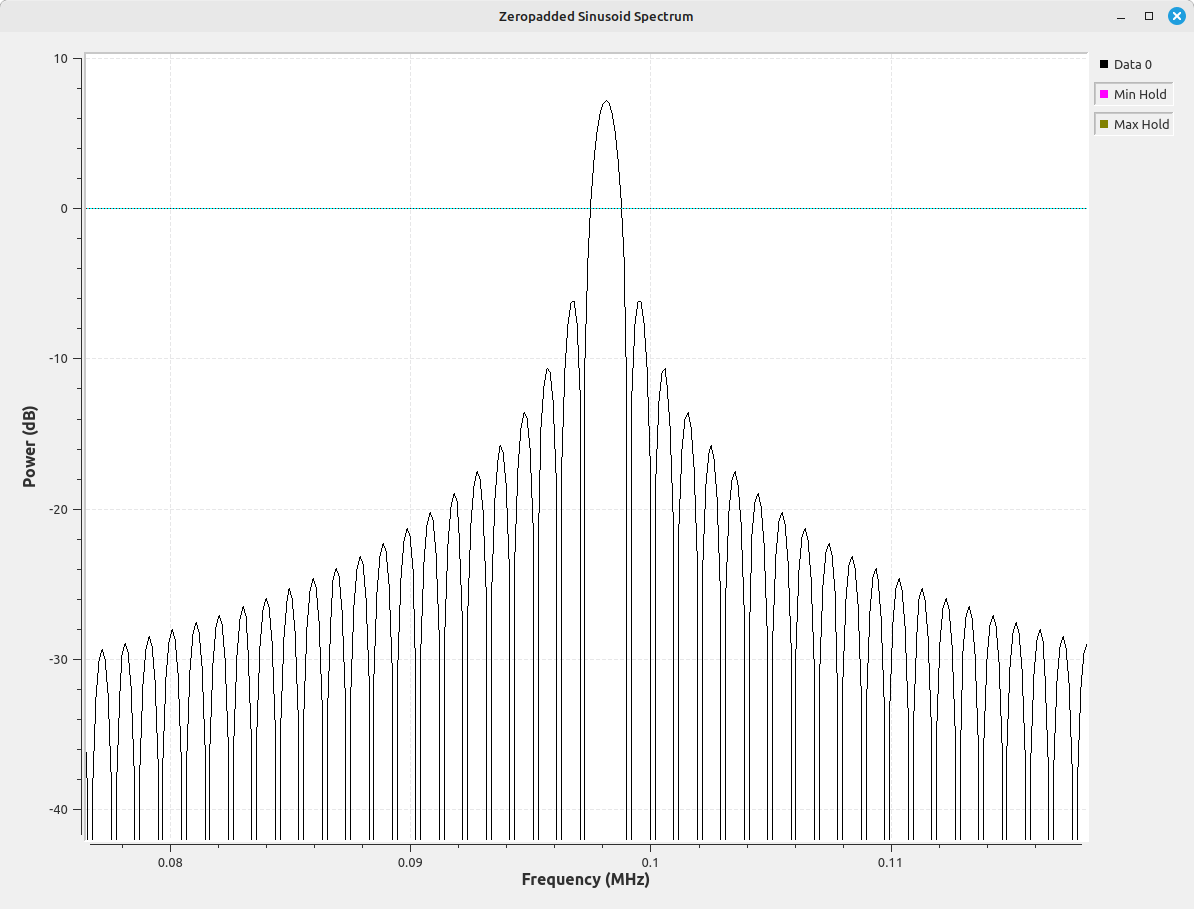

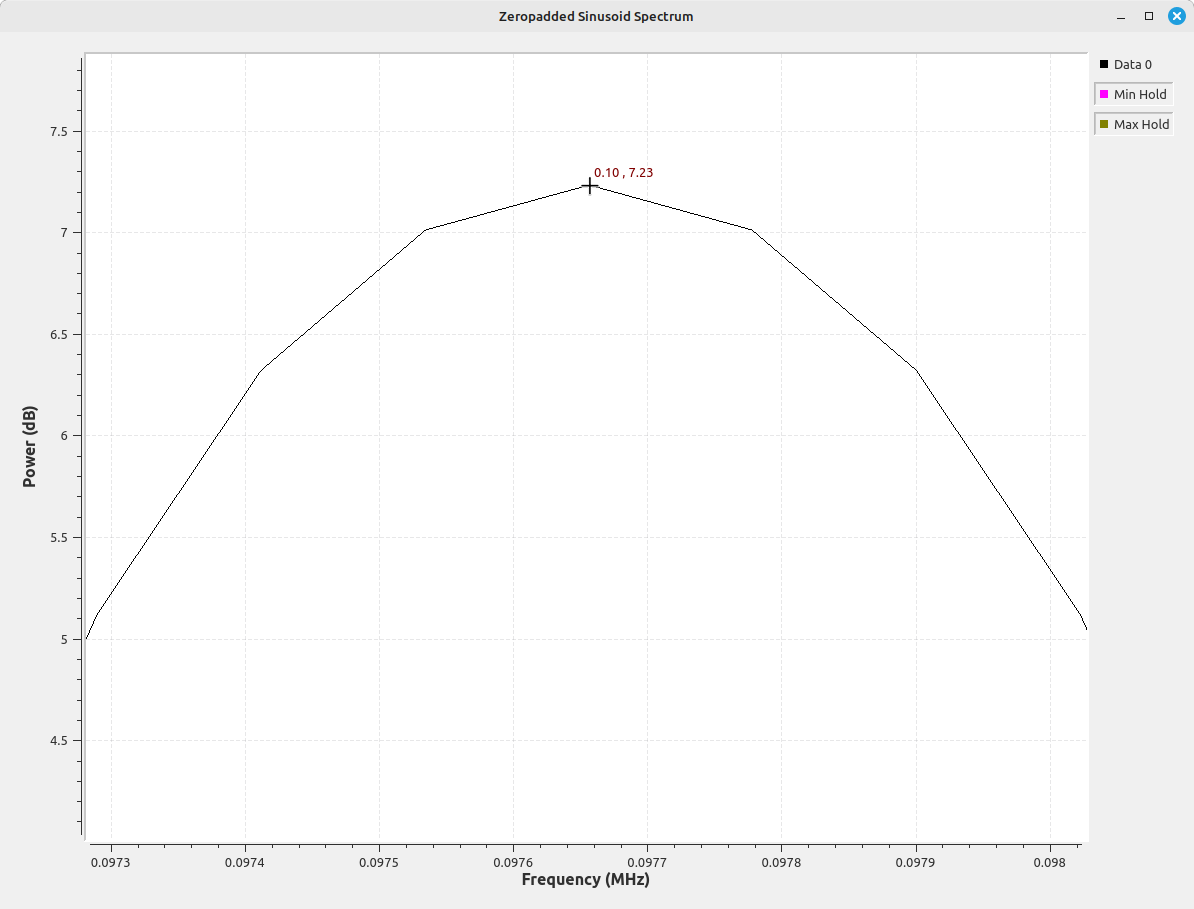

The display above shows that, with zeropadding of the time record, we can now accurately measure the power at the peak correctly. Further, with this technique, we'll accurately measure the peak, regardless of where the sinusoid winds up within the frequency bin, whether centered or at the edge. The image above was with the sinusoid at the edge of a bin. Below moves the sinusoid to the center of the bin.

The downside to zeropadding is the extra processing required due to the increased size of the time record. There's the processing required to add the zeros, plus the extra processing within the FFT routine. All of the images above used a zeropadding of 8x, meaning that the time record fed into the FFT routine consisted of the original dataset plus a set of zeros that was 7x times the length of the dataset.

Flattop Window

Based on my limited experience, probably the most widely used method to limit spectral leakage, and the scalloping loss that comes with it, is the use of a flattop window. These are windows that are specifically designed to limit scalloping loss. Whereas the scalloping loss of an unwindowed (aka "rectangular / boxcar / uniform" window) data set can be as high as 3.92 dB, and even the Blackman-harris 4-term window (aka "BH92") has a scalloping loss on the order of over 0.8 dB, flattop windows typically provide scalloping loss on the order of 0.01 dB or less.

The downside is that this comes at the cost of a much larger resolution bandwidth (RBW). While most non-flat windows increase the RBW by a factor of 1.5 - 2, flattop windows will increase the RBW by factors of 3 - 5.

The one thing I want to emphasize here is that a "flattop" window is not a single window. Flattops are a family of windows that have the property of very low scalloping loss. The specific flattop window used in Gnu Radio Companion is the one provided by Stanford Research in their SR785 spectrum analyzer. It has a relatively high scalloping loss of 0.0156 dB. Regardless, the result is a very accurate peak measurement, regardless of where the sinusoid resides within the frequency bin (center or edge).

Measuring Peak Power of Noise

Measuring sinusoids is all well and good, but what about noise? What does correcting for the coherent power gain of noncoherent energy do for the accuracy of our spectral display?

Let's find out.

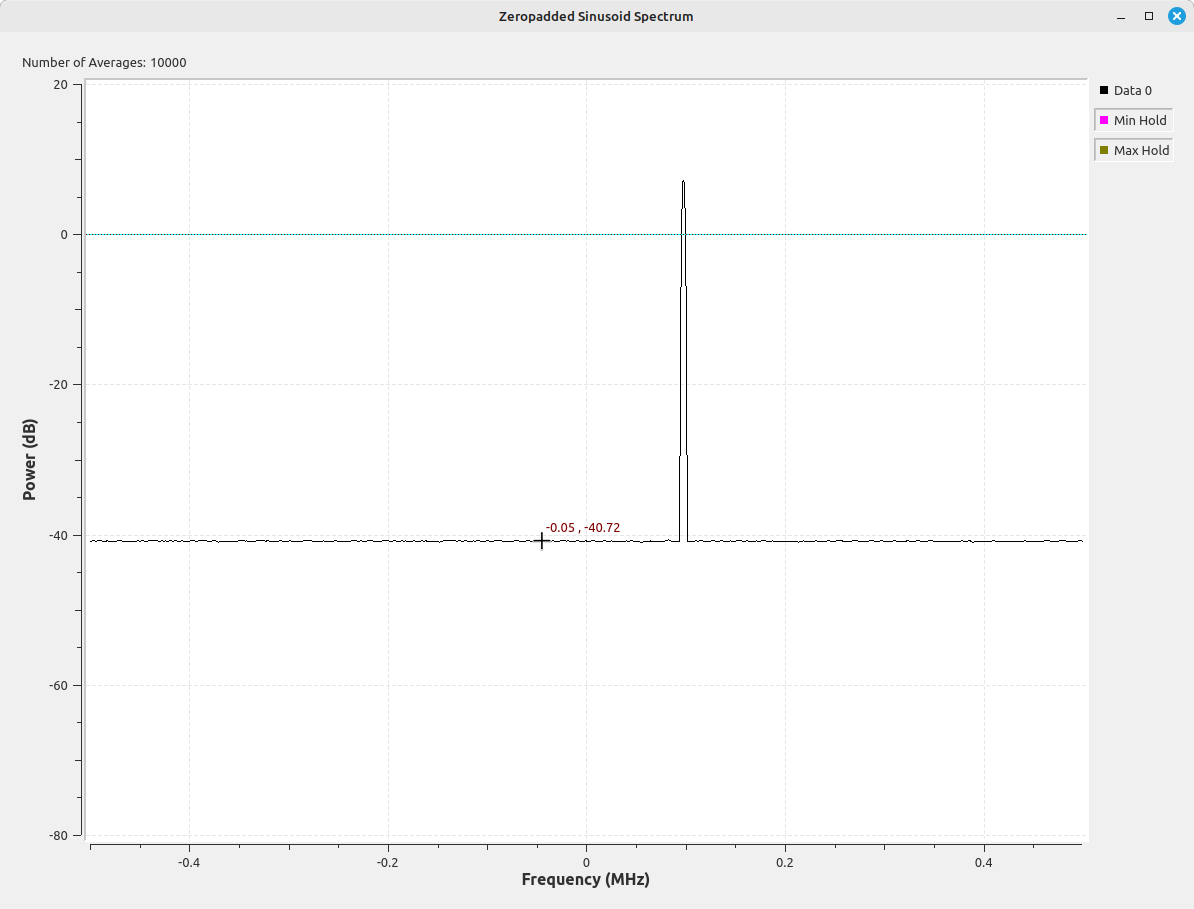

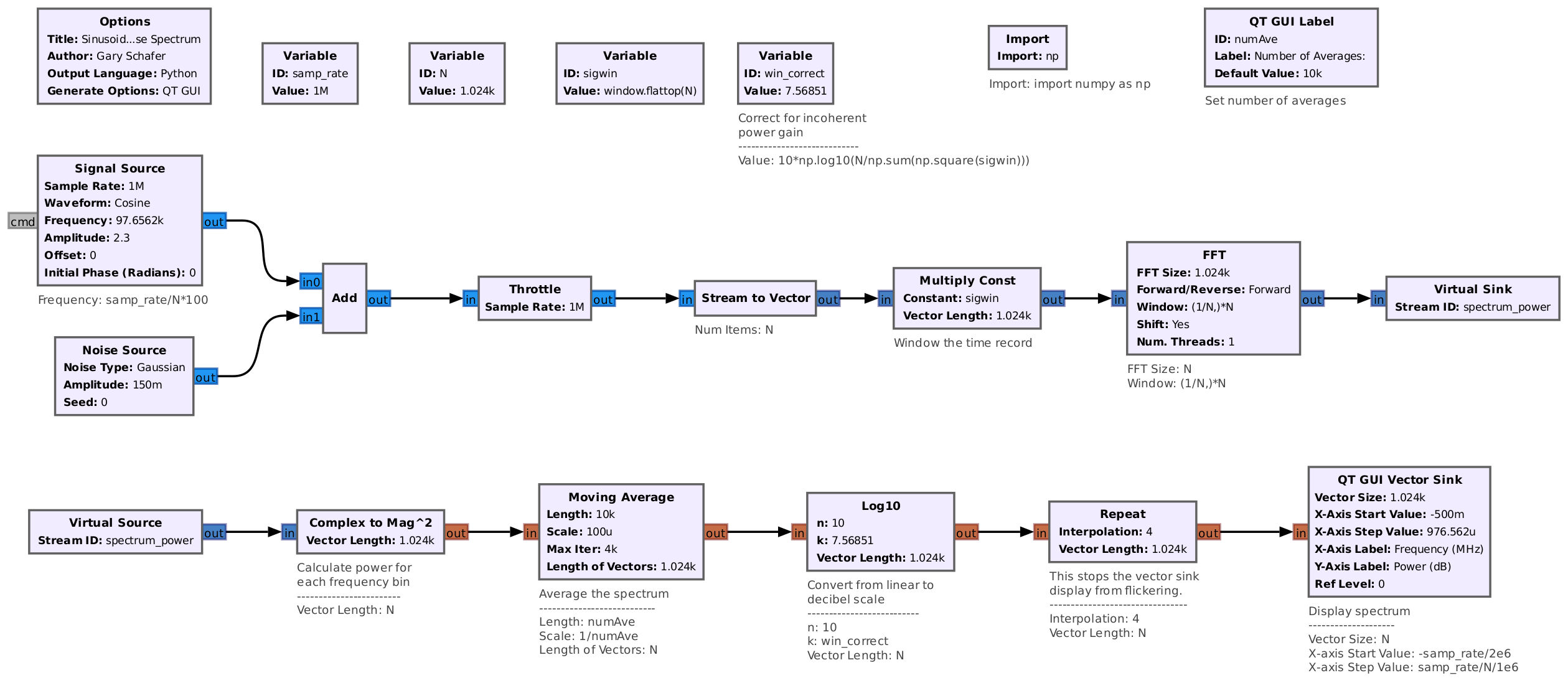

I'm going to modify the flowgraph for the flattop window to add a noise source along with the signal source, as well as add averaging. We'll need averaging to reduce the variance of the noise so that we can make accurate measurements.

As I grew up on analog spectrum analyzers (the very first one I was ever allowed to touch and actually operate was a a Hewlett-Packard 8565A analog spectrum analyzer), those used the 3 dB points to measure the resolution bandwidth. As in "Tune the spectrum analyzer to an unmodulated tone, set the span so that it is just larger than the RBW, put a marker at the peak of the signal, drop down 3 dB to either side, drop a delta marker, then move the normal marker to the other side of the peak so that it is now equal in amplitude to the delta marker. The difference in frequency is the 3 dB bandwidth."

Pretty much every modern digital spectrum analyzer (meaning those that use the FFT) do not use the 3 dB points. They use the equivalent noise bandwidth or ENBW instead. While this makes it more difficult to compare measurements between analog and digital systems, turns out there are two good reasons for this change. They are:

- Calculating the power spectral density: Using a measurement made using the coherent power gain combined with dividing by the ENBW, you can quickly calculate the power spectral density (PSD), even though that power represents noncoherent or incoherent energy. Once you know the PSD of the noise floor, you can quickly calculate the systems noise figure.

- It's easy to calculate: I've already mentioned this story in another post, but I had the opportunity to ask fred harris if he knew why digital spectrum analzyers used ENBW as opposed to the 6 dB bandwidth (which would have been the equivalent to 3 dB in the analog systems). He just chuckled and said, "Because it's so easy to calculate." Which compared to measuring either the 3 dB or 6 dB points on a curve, calculating the ENBW is much easier.

Getting back to our original problem, we have a measured DANL of -40.72 dB. Given the ENBW of our system of (1e6)(3.7702)/(1024) = 3861.9 Hz, this gives us a PSD of -40.72 - (10*log10(3861.9)) = -76.38 dB. This is pretty close to our calculated value of -76.02 dB (especially given the crude method of measuring the DANL). If we take this measured value, add the bandwidth to it (10*log10(1e6) = 60), we get -16.38 dB. This is equivalent to 0.0230 W, which is quite close to the actual value of 0.0225 (a difference of less than 3%).

Bottom line: Using a coherent power gain correction on our signals will give us accurate peak measurements plus allow us to calculate an accurate power spectral density of the resulting spectrum.

Measuring Band Power

Now that we've dealt with correcting spectrum amplitude measurements using peak power measurements, let's address using band power measurements. These are measurements where you can tell a system, "How much power resides between these two points on the spectral display?" For example, Signal Hound's Spike software allows for the measurement of all of the power within a band. (I'm also going to put in a plug for downloading this software even if you do not own any Signal Hound hardware. They provide a "Demo" mode that allows you to try out several features of their software without using any hardware.)

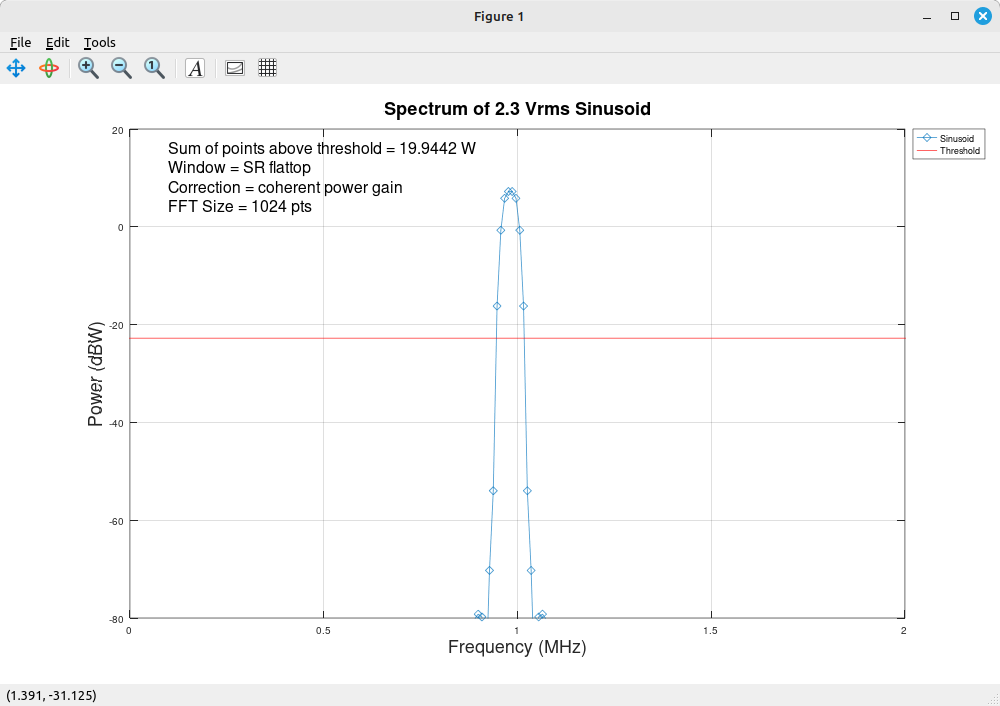

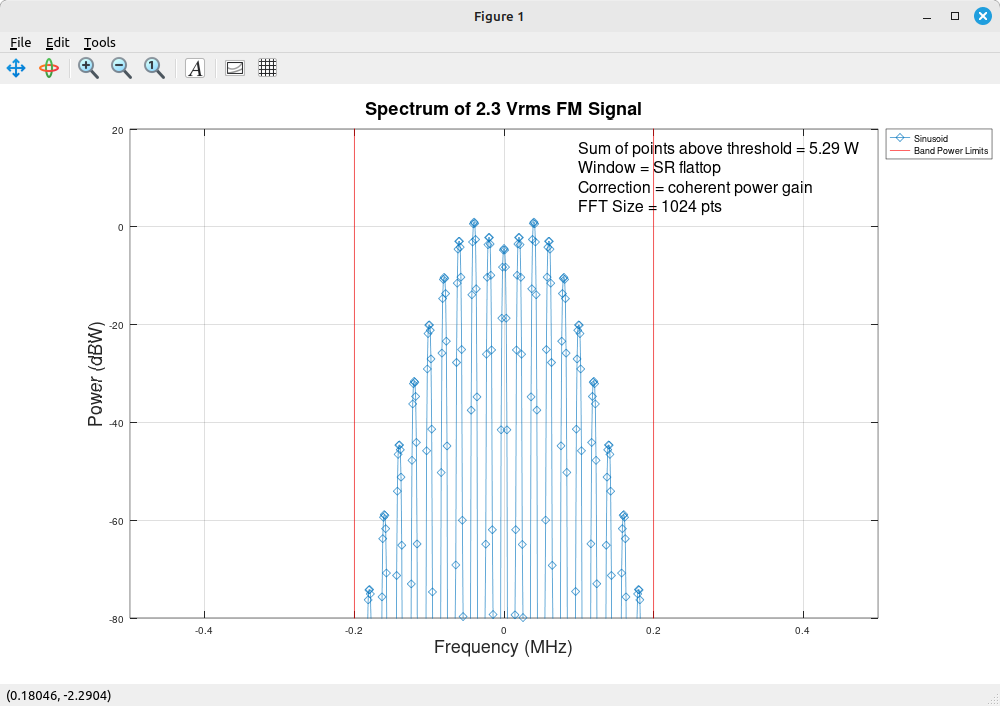

While I cannot say for certain precisely how Spike is making this band power measurement, my guess is that they're simply adding all of the power of each frequency bin within the markers. This would be a common method. Which leads to a problem if our points are corrected for coherent power gain. I've created a Gnu Octave script to perform a band measurement using a sinusoid windowed with a SR flattop window (since I've not been able to figure out how to perform a band measurement in Gnu Radio). I used coherent power gain, then switched to incoherent power gain. Here are the results:

As noted in the captions above, the coherent power gain measurement using a band power measurement is high by a factor of 19.94 / 5.29 = 3.77. This corresponds precisely to the normalized equivalent noise bandwidth or "NENBW" of the flattop window used to create the spectral display. Hence, if we have a display that is created using the coherent power gain but we want to make a band power measurement, we need to take the measured band power and divide by the NENBW of the window used when creating the display. Another option is to use the incoherent gain for correction when creating the spectral display. This will provide an accurate band power measurement with no further processing required.

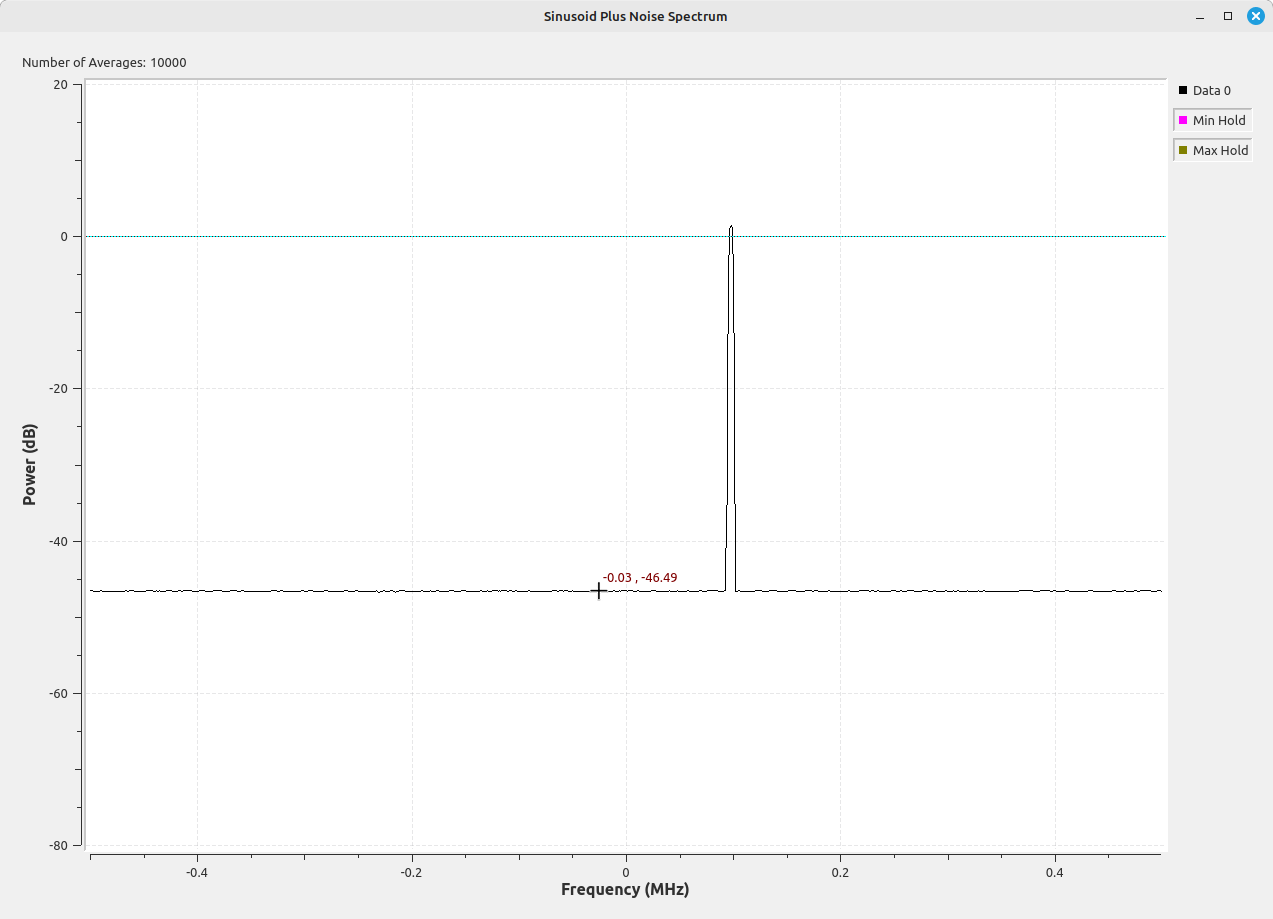

Using the incoherent power gain gives us accurate power/bin, while coherent power gain gives us accurate power/Hz. As an example, I'm going to modify the flowgraph that I used to measure the noise spectral density so that it uses the incoherent power gain rather than the coherent.

The displayed spectrum shows a noise floor that is lower by 5.77 dB (-46.49 - (-40.72) = -5.77 dB) than that measured using the display corrected with the coherent power gain. This difference is due to the NENBW. The window used for this display was the SR flattop, which has a NENBW of 3.77. In dB, this is 10*log10(3.77) = 5.76 dB. What this measured value is showing you is the power per frequency bin. With this measured level and knowing the number of frequency bins (1024), we can calculate the total power level. Given the measured level of -46.49, the total power is -46.49 + 10*log10(1024) = -46.49 + 30.1 = -16.39 dB. Again, this corresponds to a total noise power of 0.023 W. The calculated value is 0.0225, a difference less than 3%.

Switching Between Values

Which brings us to a conclusion we can make about all of these correction values. We can use any of them we want for display (peak or band) and convert to the other using the NENBW as the conversion factor. I'm just going to create a short list of the differences.

| When using... | ... you get... | ... which can be converted to the other by |

|---|---|---|

| Coherent power gain | power/Hz | dividing by the NENBW |

| Incoherent power gain | power/bin | multiplying by the NENBW |

As an example, let's say that I have my display setup using the coherent power gain (peak power), but I want to do a band power measurement. I would make the band measurement, then divide by the NENBW of the window to achieve the correct band power measurement.

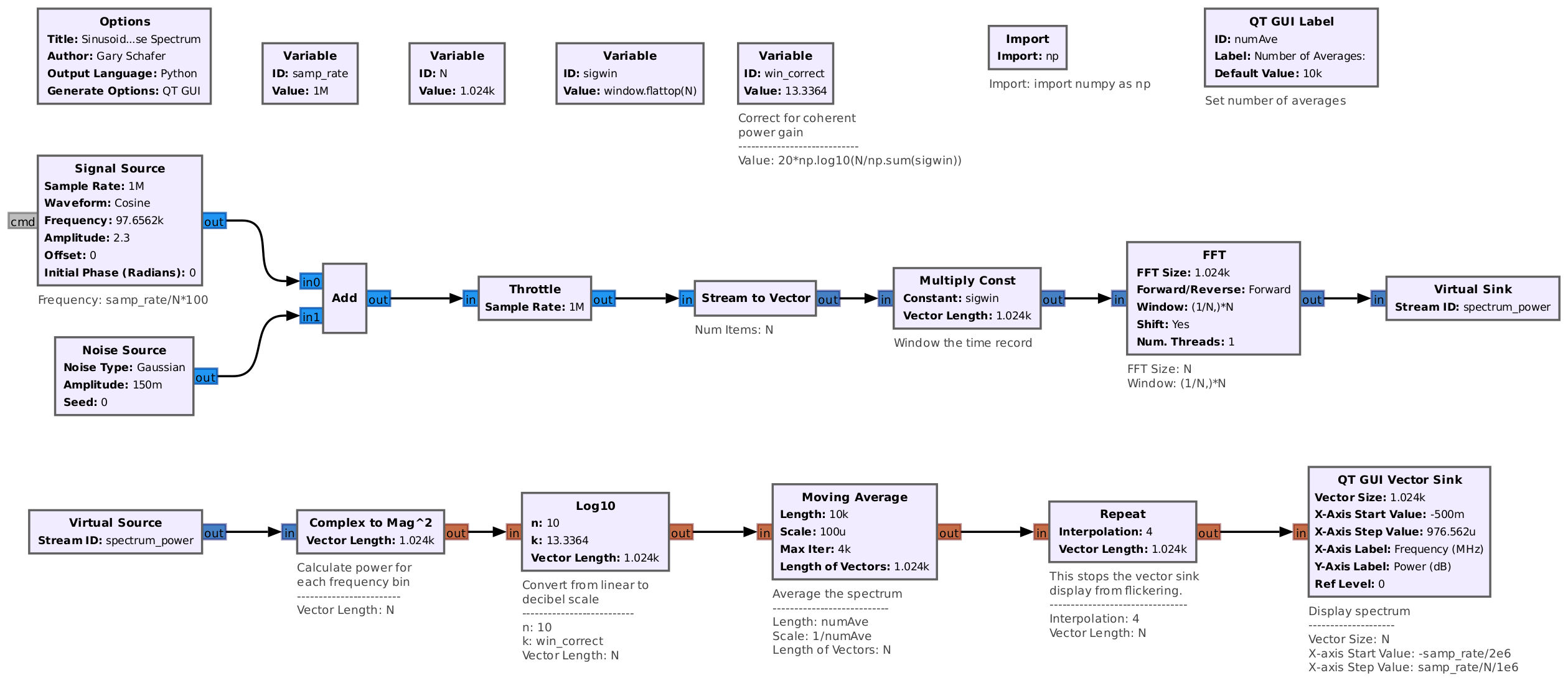

The Problem with Averaging

I want to finish up this post by making a measurement of an actually-modulated signal using all of this new-found knowledge. But before we do that, we have to talk about "the problem of averaging". This is a problem that exists with noncoherent or incoherent energy and the use of logarithmic scales used in spectral displays. Refer back to my flowgraph for creating a spectral display using averaging. Notice that the block that performs the averaging is separate from the block that performs the logarithmic conversion ("Log10" block). Since these are two blocks, they can go in two orders. The first is as shown, meaning average then convert to decibel. The second is to first convert to decibel then average. Let's find out what happens if switch them around. I'm also going to switch the power gain correction back to coherent power gain.

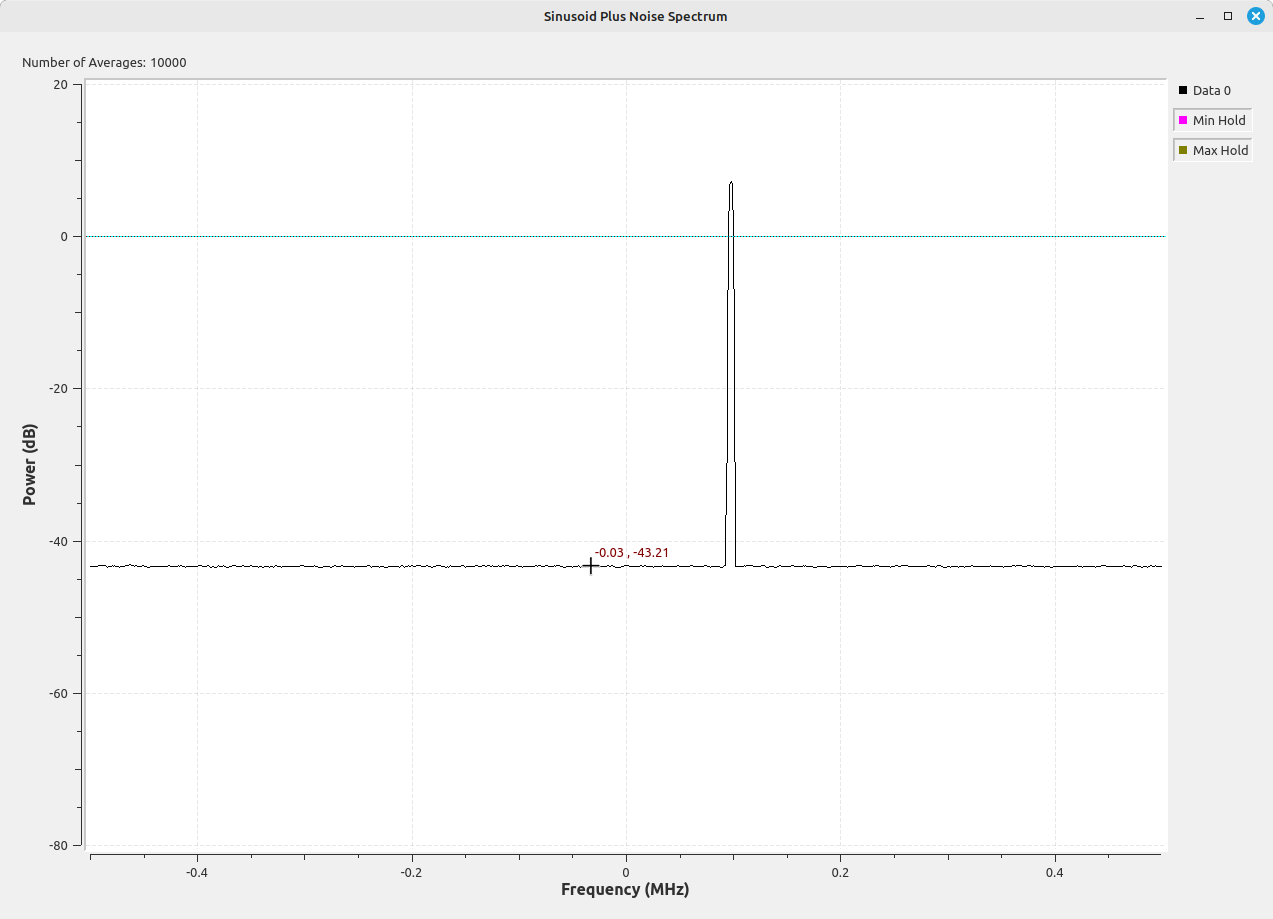

Looking at the spectral display above, we have a measured noise floor (using coherent power gain correction) of -43.21 dB. This is different from the previous display in which the averaging was performed first (using linear values) then converted to dB. That value was -40.72 dB. This is a difference of -2.5 dB. This difference is due to the inherent skewing of log scale amplitude values. What this means is that, if you're using a display that first converts to log scale and then averages and you're measuring a noncoherent / incoherent signal (noise, for example), you have to add 2.5 dB to the measured value.

The Gnu Radio QT GUI Frequency Sink is one of those systems that averages log scale values rather than linear. This means that, if you're trying to measure power levels of noncoherent signals using this block, you have to add 2.5 dB to the measured value plus the desired power gain correction factor (coherent or incoherent).

And in case you're curious as to why this was not solved in the first spectrum analyzers, those first analyzers were analog, and the use of a log scale was part of the conversion to spectral data. It literally was not possible to average before converting to the log scale. The upside was that, once the switch to digital occurred, most people realized, "Hey, let's move that averaging to before the decibel conversion, shall we?"

Measuring a Modulated Signal

These measurements of noise and sinusoids is all well and good, but what about measuring on modulated signals? Signals that have some bandwidth to them? Measuring band power in Gnu Radio is not something I've figure out how to do yet. So I'm going to model it with Gnu Octave. I've created a script that will create a basic FM signal (modulated with a sinusoidal tone), then sum the power of each point between two frequencies.

Which worked quite nicely. I actually used the coherent power gain for correcting the spectral amplitudes, then once I'd calculated the band power, I divided it by the NENBW. The resulting measured power is quite accurate.

Yay, us.

Summary

And I'm spent. Let me add one, last statement. There's a third method for making band power measurements. That is filter out the desired band and measure in the time domain. Frankly, given everything I've just covered, this might just be easier and much more fool-proof.

Through this post, I hope that I've allowed you to understand some of the pitfalls and "gotchas" of spectral power measurement. Measuring power, regardless of source, using spectral data requires care and understanding of what those amplitudes represent (and how they were created!)

References

[1]"On the Use of Windows for Harmonic Analysis with the Discrete Fourier Transform", fred harris, Proceedings of the IEEE, Vol. 66, No. 1, January 1978.